Giulia Tofana, the 17th Century Cosmetologist Who Helped Hundreds of Women Get Rid of Their Abusive Husbands… Forever | The State

In 1791, Wolfang Amadeus Mozart lay on his sickbed convinced that he had been poisoned and sure he knew with what substance.

“Someone gave me acqua tofana and calculated the precise moment of my death“.

Acqua or Aqua Tofana was a legendary poison and ideal for carrying out perfect crimes.

Was tasteless, odorless and transparent, so it went unnoticed. Its effect could be regulated by the person who administered it, allowing him to calculate the moment of death at a week, a month and up to a year, and left no traces on the body of the victim.

The history of the mysterious liquid that frightened Europe at the time of the great composer went back a century, and told that more than 600 men had died under its effects at the hands of their wives before the secret was revealed.

The details of what happened, however, are as dark as those of the best legends.

G.T.

The best-known version claims that Aqua Tofana was the creation of an Italian noblewoman named Giulia Tofana who lived during the first half of the 17th century.

He was dedicated to producing handmade cosmetics, including that product for women who had a more serious problem than blemishes on their faces.

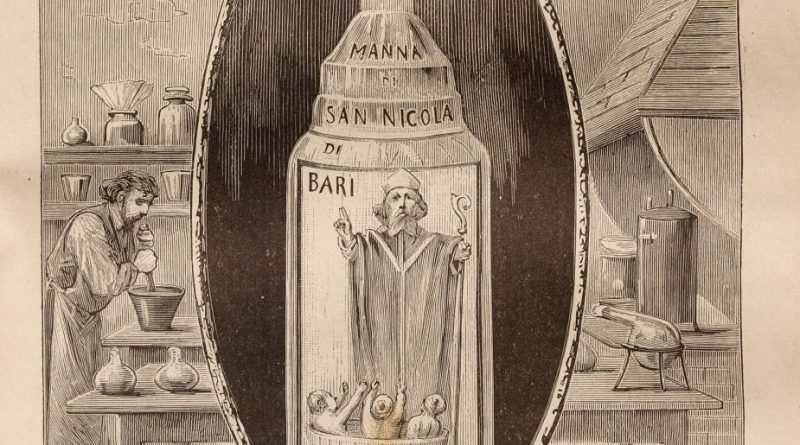

According to his contemporaries, the Aqua Tofana was sold disguised as “Manna from San Nicolás de Bari”, a healing oil that supposedly miraculously dripped from the bones of the saint, and that it was not uncommon to find in the houses of the time.

As the magazine reported “Chambers’s Journal”In 1890, a few drops were enough to end the life of the strongest of men.

“Administered in wine or tea or some other liquid by the flattering traitor, [producía] a barely noticeable effect; the husband would get a little in a bad mood, he felt weak and languid, so slightly ill that he would hardly call a doctor. After the second dose of poison, this weakness and languor became more pronounced.

“The beautiful Medea who expressed so much anxiety over her husband’s indisposition, would hardly be the subject of suspicion, and perhaps she would prepare her husband’s food, as prescribed by the doctor, with her own beautiful hands. In this way the third drop would be administered and prostrate even the most vigorous man.

“The doctor would be completely perplexed seeing that the seemingly simple ailment did not yield to its medicines, and while he still did not know what his nature was, other doses were given, until finally death claimed the victim“.

Why so many?

The story goes that Giulia Tofana gave this poisonous substance to hundreds of Italian women until one of them cowered before giving her husband a bowl of poisoned soup and ended up revealing everything that so many had kept quiet about.

If you wonder why there were so many women willing to commit such a crime at that time, remember that marrying for love is a new custom: Marriages, even of relatively powerful women, were arranged regardless of the future of those involved.

And given that the social order condemned women to always be below, it is not surprising that many ended up in dead ends in which – if it was an aggressive husband – even their own lives could be in danger.

Although sometimes the reasons were different, as in a case found by the historian Mike Dash.

For love

Maria Aldobrandini, a member of one of the most powerful and influential noble clans in Rome, had been married, when she was 13 years old, to Duke Francesco Cesi, scion of a very distinguished family (her father had been a prominent and intimate scientist of Galileo, and he himself was the nephew of the future Pope Innocent XI), who was at least 30 years older than her.

The Duke of Ceri died suddenly 9 years later, in 1657, and became the richest and most powerful of those involved in the Aqua Tofana poisoning scandal.

According to the account of Alessandro Ademollo (1826-1891), who published the results of his investigations based on old judicial records of the Archivio di Stato di Roma, Giovanna de Grandis -who worked for Tofana- confessed that Aldobrandini he had fallen madly in love with another Count, Francesco Maria Santinelli, and that prompted her to want to get rid of her husband, who was already ill.

He turned to the priest who was the one who supplied the women of the Tofana group with arsenic, Father Girolamo de Sant’Agnese in Agone, a church in central Rome.

The priest got him Aqua Tofana and a few days later the Count of Cesi lay in his coffin.

The countess, however, did not achieve what her heart hoped for: her own family locked her up to avoid a scandalous and unequal second marriage with her lover Santinelli.

And a few years later, when the truth about the poisonings came out, she was suspected of her husband’s death.

But to avoid scandal, she was never charged.

Confusing it

The problem with the story is the details. Some versions assure that Giulia Tofana operated in Sicily in the 1630s; others place the story much later or elsewhere: in Palermo, Naples, and Rome.

Sometimes it is said that she was the one who invented the potion. Others that he inherited from his mother.

The recipe for such an effective elixir is not known, although almost all sources mention arsenic.

“The mysteries multiply,” Dash notes, “when we consider the controversial question of when and how Tofana met its end.

“One source says that she died of natural causes in 1651, another that she found refuge in a convent and lived there for many years, continuing to make her poison and dispense it through a network of nuns and clergy.

“Several claim that she was captured, tortured, and executed, although they differ as to whether her death occurred in 1659, 1709, or 1730.

“In a particularly detailed account, Tofana was taken from her sanctuary and strangled, after which‘her body was dumped at night in the area of the convent where she had been taken‘”.

And Mozart?

Mozart actually never rose from his deathbed.

He died on December 5, 1791 at the age of 35.

Almost 230 years and dozens of studies later we do not know what the cause was.

But even though it may have been poison, no one mentions Aqua Tofana anymore.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.

.