Fort constructed by native Alaskans to hold off Russians discovered after more than 200 years

The site of a fort inhabited by native Alaskans has been discovered more than 200 years after it was built to fend off Russian invaders.

Using ground-penetrating radar and other non-invasive techniques, researchers confirmed the location of the last holdout of the Tlingit people in modern-day Sitka, on Alaska’s Baranof Island.

Known as Shiskinoow or ‘Sapling fort,’ the trapezoidal structure was about 240 feet long and 165 feet wide.

It was built after the Tlingit initially repelled the Russians in 1802, but was destroyed when the colonists returned two years later.

It’s exact location has eluded efforts at discovery for more than 100 years.

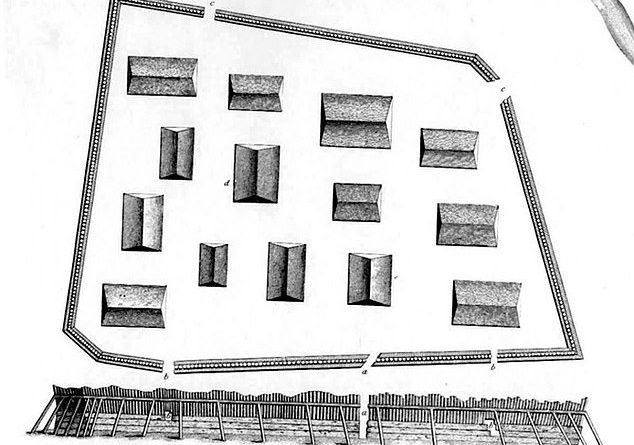

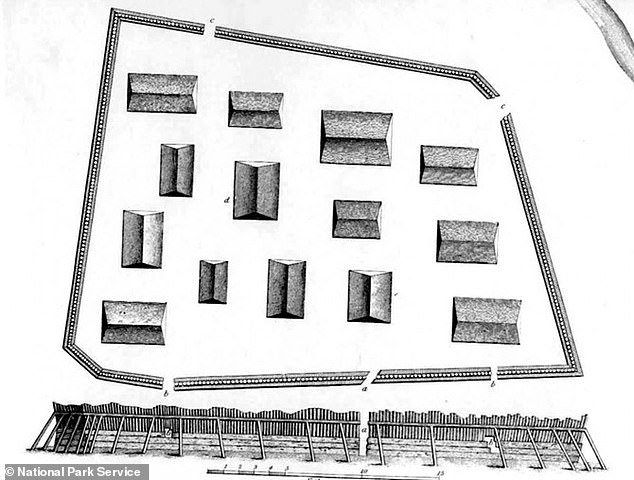

Russian captain Yuri Lisyansky made detailed renderings of Shiskinoow, the last stronghold of the Tlingit people of southeast Alaska, before the structure was razed. Its exact location remained a mystery for more than 200 years but researchers have uncovered the fort’s whereabouts using ground-penetrating radar

Russia initially sent a small contingent of troops to take possession of the area in 1799.

But even with aid from the Aleut and Alutiiq they were rebuffed by the Tlingit in 1802.

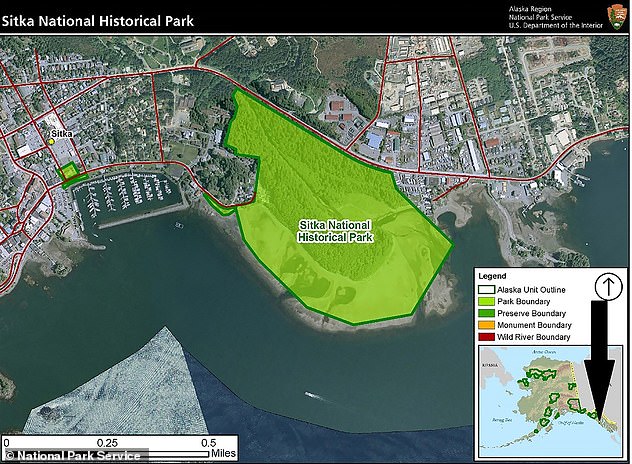

Fearing their return, the Tlingit constructed a wooden stronghold where the mouth of the Indian River meets Sitka Sound.

The natives armed Shiskinoow with guns, cannons and gunpowder they had obtained from British and American traders.

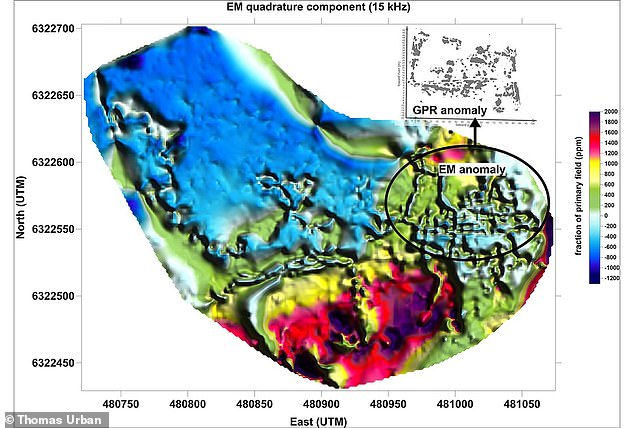

Electromagnetic induction (color) and ground-penetrating radar (inset in gray) both detected the Tlingit’s ‘sapling fort’ as described by Russian invaders

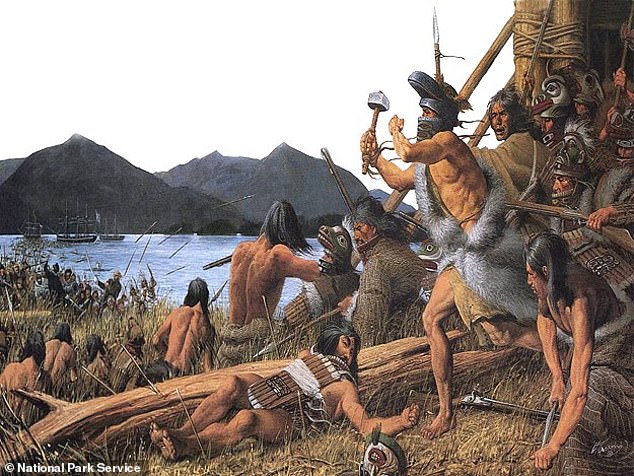

A representation of the Tlingit’s 1804 battle against Russian forces by painter Louis S. Glanzman

‘It was constructed of wood so thick and strong the shot from my guns could not penetrate at the short distance of a cable’s length [between 600 and 720 feet],’ Russian captain Yuri Lisyansky wrote at the time, NBC News reported.

When the Russians returned in the fall of 1804, the Tlingit were able to hold them off for five days.

But their reserve gunpowder blew up on its way back to the fort, leaving the Tlingit defenseless and signaling the end of their resistance.

They abandoned Shiskinoow and the Russians razed it, turning the area into a trading post and occupied Alaska until 1867, when it was purchased by the US for $7 million.

The Tlingit built the ‘sapling fort’ on a peninsula where the mouth of the Indian River meets Sitka Sound. It held off the Russians until their reserve gunpowder was lost in an explosion

Archaeologists have looked for Shiskinoow since the early 20th century but contemporary descriptions offered only a general idea of its whereabouts.

Fortunately, Lisyansky made a detailed rendering of the fortress before it was destroyed, so researchers had an idea of what they were looking for, even if they didn’t know exactly where.

‘Previous archaeological digs had found some suggestive clues, but they never really found conclusive evidence that tied these clues together,’ said Thomas Urban, a research scientist at Cornell University and lead author of a new report in the journal Antiquity.

Urban did have a good starting point, though: In the 1950s, researchers reported discovering wood from the fort’s western wall in Sitka National Historical Park, Urban told Live Science.

Cannonballs were found in roughly the same area in the early 2000s.

U

rban’s team got a more precise fix on the fort’s location by using electromagnetic induction, which scans underground areas by measuring electrical conductivity.

They analyzed 0.07 square miles, reportedly the largest archaeological geophysical survey ever conducted in Alaska.

An even smaller section of land was analyzed with ground-penetrating radar, which beams microwave pulses beneath the surface.

In the 1950s, wood from the fort’s western wall was uncovered in Sitka National Historical Park. In the 2000s, cannonballs were discovered in the same vicinity

The two methods detected similar patterns that matched historical descriptions of the fort’s general size and shape.

‘We were able to both confirm a location and rule out other potential locations,’ said co-author Brinnen Carter of the National Park Service..

He described their findings as ‘firm documentary evidence.’

‘When you bring remote sensing into it, you’re hammering together multiple lines of evidence on identifying where the fort was located.’

Urban described Shiskinoow as ‘a significant locus in New World colonial history and an important cultural symbol of Tlingit resistance to colonization.’

An indigenous people of North America’s Pacific Northwest, the Tlingit have occupied southeastern Alaska’s coastal region and the Alexander Archipelago. for thousands of years

Their first contact with Europeans was in 1741, when they encounter Russian explorers.

The Tlingit have a matrilineal kinship system, with children considered part of their mother’s clan and property and hereditary titles passed through the maternal line.

Tlingit society is divided into two main sub-groups, the Raven and the Eagle, which are further broken down into clans and then lineages or house groups.

A particular house group’s heraldic crests are displayed on totem poles, feast dishes, house posts, weavings, jewelry, and other art and artifacts.