Retail inflation at 5-year-high, vegetables 60% expensive; to hurt economic recovery

To put the 7.35% number in context, India’s nominal GDP is expected to grow at 7.5% in 2019-20. This means nominal incomes can be expected to rise by 7.5%, which means most Indians are already feeling the pinch of the price rise.

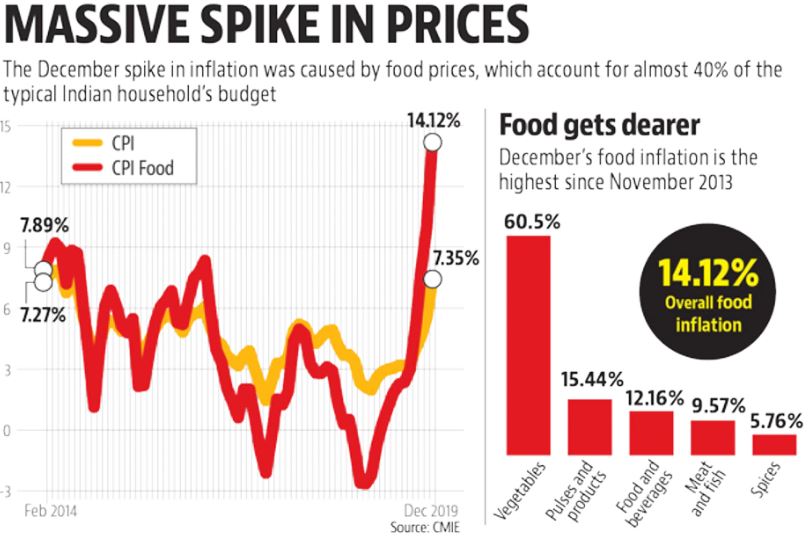

Retail inflation rose by 7.35% in December, the most since July 2014, driven largely by higher vegetable prices, and to some extent by an increase in phone tariffs, posing a political and economic challenge to the Narendra Modi government.

Analysts fear that the number, in excess of the upper band of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI)’s comfort level of 4% plus-or-minus 2 percentage points, will prevent the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) from cutting interest rates to boost economic growth. The Indian economy expanded by 4.5% in the three months ended September 2019, the lowest since March 2013. RBI expects the economy to grow at 5% in 2019-2020. First advance estimates of GDP growth released by the CSO have also pegged the GDP growth at 5%.

The spike was caused by food prices, which account for almost 40% of the typical Indian household’s budget, and grew at 14% in the month of December, according to Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. This marks the second consecutive month of double digit year-on-year growth in food prices.

To be sure, the increase is caused by a sharp rise in the price of vegetables (vegetable prices inflation clocked 60% for the month), pulses (15.44%), and meat and fish (9.57%), with the first two being attributed to supply shocks caused largely by extreme weather events.

To put the 7.35% number in context, India’s nominal GDP is expected to grow at 7.5% in 2019-20. This means nominal incomes can be expected to rise by 7.5%, which means most Indians are already feeling the pinch of the price rise.

The MPC paused its rate cut cycle in December 2019 with headline inflation numbers inching up. The December spike, which will be the latest available data when the MPC meets in February, is likely to prolong the pause on any further reductions in policy rates, analysts said.

This is bound to dampen economic sentiment. While the economy has been showing some green shoots — GST collection has been more than ?1 lakh crore for two consecutive months, Index of Industrial Production (IIP) turned positive in December after contracting for three months and Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) has been rising — big-ticket consumer spending continues to be fragile. Car sales contracted for the eighteenth consecutive month in December, according to data realised by the Society for Indian Automobile Manufacturers (SIAM).

“Rising food prices will hurt an economic recovery even more as an overwhelming number of people will be forced to cut back on non-food spending to just manage two square meals,” said Himanshu, an associate professor of economics at Jawaharlal Nehru University. It will be even more disastrous if the seasonal shock is allowed to justify a cutback in spending towards mass income generation programmes in the forthcoming Budget, he added.

To be sure, the headline number should not be inferred as evidence of a widespread rise in prices in the economy. The core inflation measure, which excludes food and fuel and light groups, grew at only 3.5% in December, rising marginally from its 3.26% value in November 2019, according to data available with the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Core inflation growth was 7% in December 2013, the last time food inflation was in double digits.

The sharp rise in inflation weeks before the presentation of the next Budget is bound to complicate India’s fiscal math. Things could become worse if the ongoing US-Iran tensions in West Asia lead to a spike in oil prices, which will affect inflation, fiscal deficit and the current account balance at the same time.

The biggest factor behind the sharp spike in food prices is a seasonal shock to vegetable, pulse and meat and egg prices. Prices of potatoes, onions and tomatoes, the three most important vegetables in the CPI basket, increased by 37%, 328% and 35% respectively in December on a year-on-year basis. Pulse prices increased by 23.7% and meat prices are up by 9.6%. The government has been importing onions to deal with the situation and analysts expect the prices to start coming down. Inflation should come down in January with the new onion crop in and prices moving down. However, the base effect will impact inflation for one more month, said Madan Sabnavis, chief economist at CARE Ratings Ltd.

An HT analysis of retail prices available at the website of the National Horticultural Board in Delhi shows that vegetable prices are not showing any signs of moderation in January too. Average retail prices for onions between January 1 and 10, 2020, were Rs 85.5/kg, 310% more than Rs 20.89 a kg in the same period last year.

Escalation in CPI inflation stoked by high food inflation is majorly because of sustained cold wave in the month of December and disruption in the supply of food items. Inflation will come down very soon as supply of these items is improving significantly and average inflation will remain at around 5.5% in the current financial year, said DK Aggarwal, president of PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Gopal Agarwal, a spokesperson of the Centre’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)?on economic affairs, said the current inflation figures were the result of short-term supply disruption, particularly in the fruit and vegetable markets. “A second reason could be that government’s efforts were focused on reviving consumer demand. But the government will now decide on further policy measures to be taken based on these figures,” he said.

The opposition Congress party tweeted: “BJP’s economic policies have driven India into an abyss. The govt neither understands the problem nor can provide any comprehensive solution to the economic woes of the country. Inflation has skyrocketed & the common man will have to pay for this govt’s incompetence.”

Communist Party of India (Marxist) general secretary Sitaram Yechury said: “Food prices shoot through the roof. Industrial production stall. Joblessness at an all-time high. Making people stand in queues with documents to prove they are Indian. These are the ‘achhe din’ [Prime Minister Narendra] Modi promised in 2014.”