The Mysterious Origin Of Stuttering In The Brain (And Novel Investigational Treatments To Try To Overcome It) | The State

Gerald Maguire has stuttered since he was a child, but if you talk to him, you may not realize it.

For the past 25 years, Maguire – a psychiatrist at the University of California at Riverside, in the United States – has been treating his disorder with antipsychotic medications that are not officially approved for this condition.

Only by paying close attention will you be able to discern an occasional stumble in multisyllabic words like “statistically” or “pharmaceutical.”

Maguire is not alone: more than 70 million people around the world – including nearly three million Americans – stutter. That is, they have difficulty starting and timing their speech, resulting in pauses and repetitions.

This figure includes approximately 5% of children, many of which overcome this condition, and 1% of adults.

They include the brand new US President Joe Biden, the actor James earl and the actress Emily Blunt.

While these people, including Maguire, have been successful in their careers, stuttering can contribute to social anxiety, and make one ridiculed or discriminated against.

Origin of the problem

Maguire has been treating people with stuttering and researching potential treatments for decades.

He receives daily emails from people who want to try drugs, join his trials, or even donate their brains to his university when they die.

Maguire has now embarked on a clinical trial of a new drug, ecopipam, that speeded up speech and improved quality of life in a small pilot study in 2019.

Others, meanwhile, are investigating the causes of stuttering, something that may also lead to novel treatments.

In the past, many therapists mistakenly attributed stuttering to a number of causes, such as defects in the tongue and larynx, anxiety, trauma, or even poor parenting, and some still do.

However, according to J. Scott Yaruss, a speech-language pathologist at Michigan State University, others have long suspected that neurological problems could be the cause of stuttering.

The first data to support this theory came in 1991, he says, when researchers found altered blood flow in the brains of people who stuttered.

Over the past two decades, research has made it more apparent that stuttering is in the brain.

“We are in the midst of an absolute explosion of knowledge that is unfolding about stuttering,” says Yaruss.

However, there is still much to discover. Neuroscientists have observed subtle differences in the brain of people who stutter, but cannot be sure whether those differences are the cause or the result of the condition.

Geneticists are identifying variations in certain genes That predispose a person to stuttering, but the genes themselves are puzzling: their links to the anatomy of the brain have only recently become apparent.

Maguire, meanwhile, follows treatments based on the dopamine, a chemical messenger in the brain that helps regulate emotions and movement (precise muscle movements, of course, are necessary for intelligible speech).

Scientists are beginning to connect those ends, even as they move forward with the first tests for treatments based on their discoveries.

Connection delays

When looking at a standard brain scan of someone who stutters, a radiologist will not notice anything unusual.

It’s only when experts look closely, with specialized technology that shows the brain’s in-depth structure and activity during speech, that the subtle differences between the groups that stutter and those that don’t become apparent.

The problem is not confined to one part of the brain.

Rather, it is about connections between different partsaccording to speech and language expert and neuroscientist Soo-Eun Chang of the University of Michigan.

For example, in the left hemisphere of the brain, people who stutter often seem to have slightly more connections. weak between the areas responsible for hearing and the movements that generate speech.

Chang has also observed structural differences in the hard body, the great bundle of nerve fibers that joins the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

These findings suggest that stuttering may result from slight delays in communication between parts of the brain.

Speech, Chang notes, would be particularly susceptible to such delays, because it must be coordinated at lightning speed.

Interference

Chang has been trying to understand why approximately 80% of children who stutter grow up to have normal speech patterns, while the other 20% continue to stutter into adulthood.

Stuttering usually begins when children begin to put words together in simple sentences, around the 2 years.

Chang studies children for up to four years, starting as early as possible, looking for changing patterns on brain scans.

Convincing such young children to sit still in a giant, noisy brain imaging machine is no easy task.

The team has embellished the scanner with decorations that hide all the scary parts. “It looks like an adventure in the ocean,” he says.

In children who lose their stuttering, Chang’s team has observed that the connections between the areas involved in hearing and speech movements they get stronger over time.

But that does not happen in children who continue to stutter.

In another study, Chang’s group looked at how different parts of the brain function simultaneously or not, using blood flow as an indicator of activity.

The team found a link between stuttering and a brain circuit called the default mode network, which is involved in reflecting on past or future activities, as well as on what dreams one has awake.

In children who stutter, the network by default seems to insert itself, like a third person intruding on a romantic date, in the conversation between the networks responsible for focusing attention and creating movements.

That could also slow down speech production, he says.

These changes in the development or structure of the brain may be caused by a person’s genes, but understanding of this part of the problem has also been slow to mature.

It’s all in the family

In early 2001, geneticist Dennis Drayna received a surprising email: “I am from Cameroon, West Africa. My father was the boss. He had three wives and I have 21 brothers and half brothers. Most of us stutter, ”Drayna recalls.

“Do you think there could be something genetic in my family?” The message continued.

Drayna, who worked at the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, had a long-standing interest in the inheritance of stuttering.

His uncle and older brother stuttered and his twin sons did when they were children.

But he was hesitant to take an email-based transatlantic trip and worried that his clinical skills weren’t enough to analyze the family’s symptoms.

Drayna mentioned the email to the current director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins (who was director of the National Institute for Human Genome Research at the time), who encouraged him to study the case, and this is how he bought a ticket. To Africa.

He also traveled to Pakistan, where intermarriage of cousins can reveal genetic variants linked to genetic disorders in the resulting children.

Even with those families, finding the genes was a slow process. Stuttering not inherited in simple patterns like blood types or freckles.

But eventually, Drayna’s team identified mutations in four genes (GNPTAB, GNPTG, and NAGPA from the Pakistan studies, and AP4E1 from the clan in Cameroon) that he says may be the basis for one in five cases of stuttering.

Interestingly, none of the genes Drayna identified has an obvious connection to speech.

Rather, they are all involved in shipping cellular materials to the waste recycling bin called the lysosome. It took more work until Drayna’s team was able to link genes to brain activity.

At the laboratory

The team began by engineering mice so that their version of GNPTAB had the same mutation they had observed in people, to see if it affected their vocalizations.

Mice can be very talkative, but much of their dialogue takes place in an ultrasonic range that people cannot hear.

By recording the ultrasonic calls to the puppies, the team observed patterns similar to human stuttering.

“They have all these gaps and pauses in their train of vocalizations,” says Drayna, who co-wrote an overview of this genetic research.

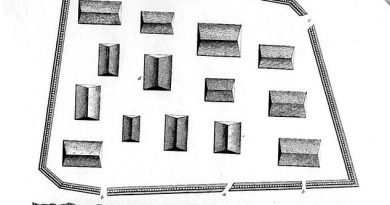

Still, the team struggled to detect any clear defects in the animals’ brains, until a determined researcher discovered there were fewer of the cells called astrocytes in the corpus callosum.

Astrocytes do great jobs that are essential for nerve activity – they provide fuel for nerves, for example, and collect waste.

Perhaps, Drayna muses, the limited population of astrocytes slows down communication between the brain hemispheres a little bit, and it’s only noticeable in speech.

The researchers created mice with a mutation in a gene that is linked to stuttering in people.

The mutant mice vocalized jerkily, with longer pauses between syllables, similar to what is seen in human stuttering.

Drayna’s research has received mixed reviews.

“It has really been pioneering work in the field,” says Angela Morgan, a speech-language pathologist at the University of Melbourne and the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia.

On the other hand, Maguire has long doubted that mutations in such important genes, used in almost all cells, could cause defects only in the corpus callosum and only in speech.

He also finds it difficult to compare the squeaks of mice with human speech. “That’s too much,” he says.

Scientists are sure there are more genes linked to stuttering to be found. Drayna has since retired, but Morgan and his collaborators have started a large-scale study in hopes of identifying additional genetic contributors in more than 10,000 people.

The dopamine connection

Maguire has approached stuttering from a very different angle: investigating the role of dopamine, a key signaling molecule in the brain.

Dopamine can increase or decrease the activity of neurons, depending on the location of the brain and the nerve receptors to which it attaches.

There are five different dopamine receptors (called D1, D2, etc.) that pick up the signal and respond.

The extra dopamine appears to stifle activity in some of the brain regions that Chang and others have linked to stuttering.

Supporting the connection to dopamine, other researchers reported in 2009 that people with a certain version of the D2 receptor gene, one that indirectly enhances dopamine activity, are more likely to stutter.

So Maguire wondered: could blocking dopamine be the answer? Many antipsychotics do exactly that.

Over the years, Maguire did small, successful clinical trials of these drugs, including risperidone, olanzapine, and lurasidone.

The result: “The stuttering doesn’t go away completely, but it can be treated,” says Maguire.

None of these drugs are approved to treat stuttering by the US Food and Drug Administration, and they can have unpleasant side effects, such as weight gain, muscle stiffness, and difficulties in movement.

In part, it’s because they act on the D2 version of the dopamine receptor. Maguire’s new medication, ecopipam, works with the D1 version, which he hopes will lessen some of the side effects, although there are others to watch out for, such as weight loss and depression.

In a small study of 10 adult volunteers, Maguire, Yaruss, and other colleagues found that people who took ecopipam stuttered less than before treatment.

The quality of life score, related to feelings such as helplessness or acceptance of their stuttering, also improved for some participants.

Ecopipam treatment is not the only one being considered.

In Michigan, Chang hopes that stimulating specific parts of the brain during speech can improve fluency.

The team uses electrodes on the scalp to gently stimulate a segment of the auditory area, to strengthen the connections between that point and the one that handles speech movements.

Researchers stimulate the brain while the person undergoes traditional speech therapy, hoping to enhance the effects of the therapy.

Due to the covid-19 pandemic, the team had to stop the study with 24 people out of the 50 planned. Now they are analyzing the data.

Connecting the dots

Dopamine, cellular debris removal, neural connectivity – how do they fit together?

Chang notes that one of the brain circuits involved in stuttering includes two areas that make and use dopamine, which could help explain why dopamine is important in this disorder.

She hopes that brain imaging will bring the different ideas together.

As a first attempt, she and her collaborators compared the problem areas identified by their brain scans with maps of where various genes are active in the brain.

They found that two of Drayna’s genes, GNPTG and NAGPA, had a high level of activity in the hearing and speech networks in the brains of non-stutterers.

This shows that those genes are actually needed in those areas, reinforcing Drayna’s hypothesis that defects in the genes would interfere with speech.

The team also observed something new: the genes involved in energy processing were active in the areas of speech and hearing.

There’s a big spike in brain activity during the preschool years, when stuttering tends to start, Chang says.

Perhaps, he says, those speech-processing regions aren’t getting all the energy they need at a time when they really need maximum power.

With that in mind, he plans to look for mutations in those energy control genes in children who stutter. “Obviously, we have a lot of points to join,” he says.

Maguire is also connecting the dots. He says he’s working on a theory to tie his work together with Drayna’s genetic findings.

Meanwhile, after struggling with medical school interviews and having chosen a career in speech therapy despite her speech difficulties, Maguire is pinning her hopes on ecopipam.

Together with a team of colleagues, he is starting a new study that will compare 34 people who will be given this drug with 34 who will receive a placebo.

If that treatment ever becomes part of the standard toolkit for treating stuttering, Maguire will have achieved a lifelong dream.

*This artThe article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine and has been reproduced here under the Creative Commons license.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.

.