They met by chance as Covid struck and the result was a lockdown love story like no other

Anthony had arrived late, keeping us all waiting at the dinner table, and I was tired, grumpy and longing to go to bed.

It was the first evening of my holiday in France, so as soon as I could, I made my excuses to leave the room.

And that’s when I heard the dreaded sentence, murmured by my host as I closed the door. ‘Her name is Blanche and she is 12 weeks pregnant,’ he said, in confiding tones — leaving me spitting with anger that my secret had been revealed to a complete stranger.

The fact that I was having a baby on my own, by means of a sperm donor, wasn’t something that I felt ready to talk about. Being single and childless at the age of 42 was, to me, a source of great shame.

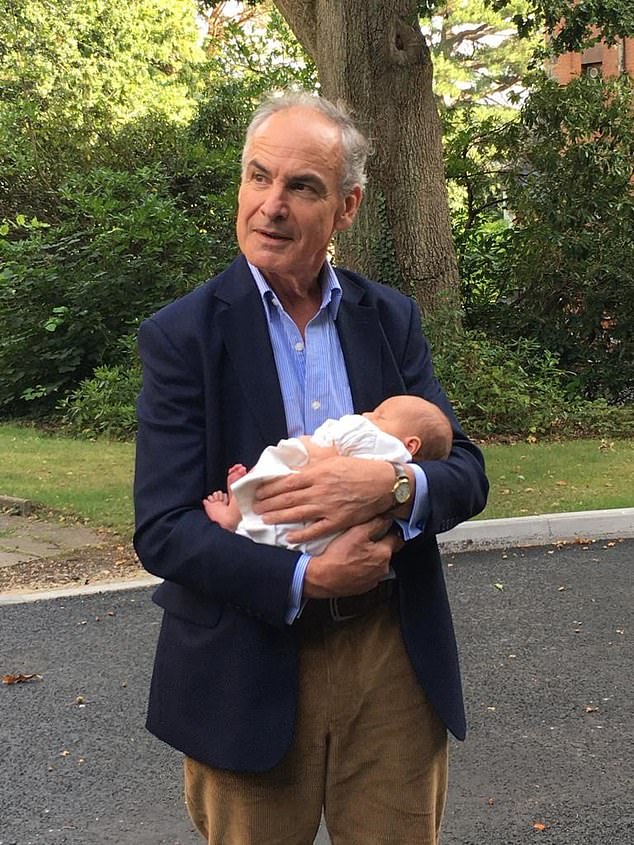

Blanche, 42, and Anthony, 63, (pictured together with Ottilie) met by chance as Covid struck and the result was a lockdown love story like no other

It wasn’t that I thought there was anything wrong with a woman of my age not having children: it was that I’d always wanted to have children and I felt that I had failed. Growing up, I had it all worked out. At 30, I was going to have my first child and then, shortly afterwards, my second.

Getting married at 31, I was a little off the mark but the situation still seemed promising. However, all too soon, my marriage hit the rocks and, by the time I was 35, we had filed for divorce.

At 35, female fertility starts to rapidly decline; I couldn’t have been more conscious of the fact. By 40, with a string of unsuccessful liaisons behind me, I was growing desperate.

And then I met ‘Mr Right’. He was witty, intelligent, interesting and great company. I could see myself growing old with him, and I very much wanted his children.

But within a year we were seeking relationship counselling.

‘I’m desperate to have a baby,’ I explained.

Blanche said that being single and childless at the age of 42 was a great source of shame which prompted her to have a baby on her own by means of a sperm donor (pictured with her daughter)

‘I love her but I don’t want a child,’ he said.

‘Well, that’s a deal breaker,’ said the counsellor. And she was right.

I was utterly devastated. I had always thought the challenge lay in finding the right partner: never had it crossed my mind that that very man might not want a child. But he didn’t, and I did, and there was nothing we could do about it.

That Christmas, I sat through a school carol concert in floods of tears. The stage was lined with children, singing sweetly, while their parents, all around me, looked on proudly.

And I sat in the midst of them and felt utterly desolate, feeling their love wash over me and fearing I’d never have a child.

Being single and childless at the age of 42 was, to me, a source of great shame

I was 42 and single, and my childlessness had become a torment. I could no longer visit friends with young children. I was blocking posts from new mothers on Facebook, and I couldn’t even stand by the photocopier at work because it looked onto a noticeboard announcing new births.

Worst of all, I found it hard not to believe my childlessness was all my fault. I’d been too picky. I’d been too difficult. I’d been too wary. I’d been too hesitant.

I’d spent too long with the wrong men and lost the good men I might have kept. And now, I felt, I’d messed everything up. I had always wanted to have children and I would not be having them.

Not, that is, unless I braved it on my own and used a donor.

Becoming a single parent had never been part of my plan, but now I saw it as my only option.

Fortunately, I had one thing on my side: I had frozen eggs. Soon after my divorce came through, at the age of 37, I had taken myself off to a clinic near London’s Baker Street and had my eggs ‘harvested’.

Anthony (pictured with Ottilie) had been an empty-nest widower when he met Blanche Girouard

Every year since then, I’d paid £300 to have them stored — and now they sat, 16 of them, ready to be defrosted and then fertilised.

Choosing a donor wasn’t easy. When you fall in love and have a baby, you don’t worry about the fact your partner might have flunked his A-levels, have a squiffy eye or a grandmother with dementia. When you’re looking for a sperm donor, you most certainly do.

For days I scrolled through donor ‘profiles’ on sperm bank websites, scrutinising and comparing every detail. In the end, I opted for the man I felt most drawn to.

Like me, he sang in a choir, came from an academic background and had a father who had told him bedtime stories. He h

ad a lovely deep voice (audible on a recording), a cute baby photograph and an impressive string of achievements to his name. But, best of all, he had written a wonderful letter to his donor children, making it clear that he would be there to ‘talk and listen’ in the future, if they wanted to make contact, and signing off ‘with loving thoughts through time and space’.

As we started as a couple, my stomach was burgeoning, a baby girl growing within me

This donor’s sperm came from a sperm bank in Europe. It cost me €639 to purchase one ‘straw’ and another €295 to have it shipped over to London.

Still clinging to a shred of hope that I would one day have a baby with a man I loved, I decided to have only half my frozen eggs defrosted and fertilised — then I sat back and waited to hear what had happened.

From eight eggs I was lucky enough to get five embryos, three of which made it to day five — the age at which they were most likely to survive after implantation.

Each embryo was graded and, as soon as my womb lining was thick enough, the best was transferred, using a catheter, into my uterus. Two and a half weeks later, a urine test revealed I was pregnant.

But by six weeks, the foetus that had seemed so promising had stopped growing, and I was told I had no option but to miscarry.

I didn’t want to be awake when I lost my first chance of having a child, so I chose to have my womb scraped under general anaesthetic. When I came round, I was crazy with grief. So crazy, in fact, that I got in touch with my ex-boyfriend, hoping against hope that he might have changed his mind about having children and rescue me from this awful situation.

Blanche said that she aware that Anthony is not Ottilie’s father — and so is he — but being a trio together makes her soul soar

But, of course, it wasn’t to be. So back I went for another attempt.

This time, I threw everything at it: biopsy (to select the best embryo for transfer); embryo glue (to keep it stuck to my womb); daily hormone injections, patches and suppositories (to thicken my womb lining and aid implantation and growth), and a course of acupuncture (to improve my chances).

On Boxing Day 2019, I discovered that, once again, I was pregnant. This time, at the six-week scan, I heard my baby’s heartbeat, as fast and loud as the hooves of a galloping horse.

Now, it was February half-term and I was supposed to be skiing in the Pyrenees. Except that I was 12 weeks pregnant, couldn’t ski and had been forced to tell my host.

Which is how it came about that he told Anthony.

As it happened, Anthony couldn’t ski either. Or, at least, he took one look at me and decided not to ski.

For five days, we went off walking while the rest of the party took to the slopes. It was bizarrely warm for February. The sun shone on our backs as we walked through woods and fields, climbed hills to look at ruined Cathar castles and tried to push open the doors of medieval churches.

On the very first day, when we stopped for lunch, he had asked me if I had wanted to have children. ‘I know that you know,’ I said and I looked at him directly.

Blushing, he began asking a torrent of questions. ‘I think you’re heroic,’ he said, when I’d finished explaining. ‘I don’t feel heroic,’ I answered. ‘I feel sick.’

I had suffered from car sickness from early on in my childhood. Being pregnant in the Pyrenees, it was even worse. So when Anthony drove around mountain bends slowly, for the sake of my heaving stomach, I was very grateful. When he stepped in front of me, as I slid down some scree on a hillside, I thought him a very nice man.

And when he offered to drive me to the airport, when he wasn’t going there himself, I suspected that he might be thinking I was quite nice, too.

For a week we had done nothing but walk and talk. Now, on our last car journey together, we fell silent, not knowing what to say.

‘It would be a pity,’ he said eventually, ‘if we lost touch.’ And I agreed. Then he dropped me off and drove off into the night, leaving me feeling his absence, but sending a flurry of messages only a few hours later, as I knew he would.

It soon transpired that he was not at all put off by my pregnancy. In fact, far from it. He had been married, very happily, for 25 years when his wife died unexpectedly from a heart condition.

Now, nine years later, at the age of 63, he was rattling about, on his own, in a seven-bedroom house in Wiltshire, falling asleep in front of the 10 o’clock news and wondering what to do with his life.

A father to four children, aged between 26 and 31, the prospect of adding another was one he positively welcomed. He liked the idea of filling his house back up with family. And the fact my child would be a similar age to his three grandchildren (all under three) made it even better.

Almost at once, he told his family about me and my baby and, though taken aback, they were unfailingly supportive.

My preference was to get to know each other slowly, meeting up occasionally for nice outings and spending plenty of time with one another’s friends and family.

But that wasn’t what happened. Within a month, the country had descended into lockdown — forcing new couples to stay together or stay apart. The prospect of being together, having only met a few weeks earlier, seemed preposterous. But it was that or nothing, and we both felt ‘to hell with it, let’s go for it’.

So we did — first in Wiltshire and then at my home in London. And slowly, we started to come together as a couple. We shared experiences. Saw each other at our weakest point and lowest ebb. Looked for solutions and found compromises. And, most importantly, wanted, and kept trying, to make things work.

Meanwhile, my stomach was burgeoning, my breasts were engorging, a baby girl was growing within me and I was beginning to panic about giving birth.

The new restrictions meant I was allowed only one person with me when I was in active labour. Who should that be? My mother? A friend? A doula (who helps women when they’re giving birth)? Or Anthony?

For months, I debated the options. But, in the end, the answer was clear. It was Anthony who had consistently supported my choices about how and when I would give birth. It was Anthony wh

o had sat through lengthy Zoom sessions about hypno-birthing, doing his best to tell me to ‘be calm and relaxed’ when I was anything but, and driving me to the local hospital, at three in the morning, when I became worried it had been too long since I had felt the baby kick.

Finally, at the end of August, my time came. For two nights, I stayed at my home in London, suffering contractions. On the third night, the exhaustion and pain began to overwhelm me and we went to St Mary’s in Paddington.

For two days we waited in our birthing suite, and on the third day she came. Not in a rush. Not in a haze of medication. But in an agony of un-medicated pushing, with four midwives holding up my legs and Anthony joining them, egging me on.

‘Would you like to hold her?’ they asked me, and I retorted ‘No’. Nothing had prepared me for such pain. And no one had told me that after pushing out her head, I would have to push again to free her shoulders.

But seconds later, I had changed my mind, and, then, there we lay, mother and baby — slimy, sweaty, exhausted but happy.

Thanks to lockdown, I’d told very few people I was pregnant. Now, though, I wanted everyone to see my gorgeous baby — and I didn’t care a jot how she had come about.

Anthony held Ottilie skin to skin on the night she was born, with an expression of the utmost tenderness on his face. Now he sits up, half asleep, to keep me company during night-time feeds. Changing her nappies, bathing her and singing her songs, he’s shown nothing but love and dedication to us both from that very first day.

Of course, I’m abundantly aware that he is not her father and so is he. I refer to him as ‘Anthony’ and he calls Ottilie ‘my girlfriend’s baby’ and sometimes I do find that upsetting.

But the truth is as it is: Anthony has his own children and Ottilie has her own father, and I wouldn’t want to deny the significance of that for either.

What the future holds for me and Anthony and for Anthony and Ottilie we can’t yet know. But what I do know is that I never imagined this could happen.

Gone are all my feelings of self-loathing and desolation. My heart is full of love and my soul soars with delight. Being a mother to Ottilie is the best thing that has ever happened to me. Being the three of us, together, makes me happy and content.

‘Present ecstasies thrive on the very anguish of the past,’ wrote the Oxford poet Elizabeth Jennings. As far as I’m concerned, she was right.

ANTHONY’S STORY:

‘Come and stay with us in the Pyrenees — it’ll be great fun!’ A throw-away invitation, accepted on a whim. After all, I had never been to the Pyrenees, so why not? I arrived at night to join the party — late for dinner but in time to spot a girl with a flash of white hair and a welcoming smile. So I met Blanche.

It was a skiing week, which suited neither Blanche nor myself. I had a car, so we were paired off to look after ourselves. We both like walking, and after walking there were restaurants to be enjoyed. And we talked.

The more we talked, the more there was to talk about. We discussed her pregnancy: the anonymous donor father, the relationships and disappointments along the way.

Blanche asked me about my 25-year marriage, which had unexpectedly ended nine years before with my wife’s sudden death. What was being a widower like? What had been my relationships and disappointments? My four children: what did they do, how had they coped?

Given our age difference, I never thought this might lead to a relationship. But at the end of the week, I realised I was going to miss Blanche and the intimacy of these conversations. Five days with someone who is intelligent, attractive and apparently interested in you is a rare gift.

On the evening drive to the airport she played me Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium. I played it on repeat after dropping her off. Also repeating in my head was the promise that we should see each other again.

Lockdown began and initially we were apart, reading our favourite books to each other, emailing daily recordings: Blanche read Strange Meeting by Susan Hill, while I chose The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni. I was wryly amused by the aptness of the titles.

We then decided to spend our time together. Blanche’s pregnancy was now obvious and one friend warned that I didn’t appreciate the commitment I was taking on.

But it was exactly that commitment which appealed to me. I had had a happy marriage and I love my children: I know both the challenges and the rewards.

Blanche’s decision to have a baby had always struck me as brave and impressive. The fact that the baby’s father was an anonymous donor created space for me to have a significant role in her life. I was very moved when Blanche asked me to be there for Ottilie’s birth.

Holding Ottilie for the first time I felt emotional and rather stunned. It is incredible to think how far we have travelled since our meeting in the Pyrenees less than a year ago.

Ottilie adds a creative dimension to our relationship: as she grows, our relationship grows too. My hope is in my future with Blanche, and a future for Ottilie within my family. I look forward to that.

n An audio diary of Blanche, Ottilie and Anthony’s story is available in the podcast Wonder of Wonders at thingsunseen.co.uk