How long will it take for the Covid vaccine to come to the rescue and get Britain out of lockdown?

Boris Johnson vowed to give one dose of a coronavirus vaccine to the 13.2 million care home residents, over-70s, frontline health workers and Britons classified as ‘vulnerable’ by mid-February.

It is the first time that the government has put outlined a target number of vaccinations, amid fears the government is delivering doses too slowly to lift restrictions by Easter as the Prime Minister has suggested will be possible.

But the PM included a number of caveats in his target and said it would be dependent on everything going in the government’s favour.

The PM said: ‘By the middle of February, if things go well and with a fair wind in our sails, we expect to have offered the first vaccine dose to everyone in the four top priority groups identified by the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation.

‘That means vaccinating all residents in a care home for older adults and their carers, everyone over the age of 70, all frontline health and social care workers, and everyone who is clinically extremely vulnerable.

‘If we succeed in vaccinating all those groups, we will have removed huge numbers of people from the path of the virus. And of course, that will eventually enable us to lift many of the restrictions we have endured for so long. ‘

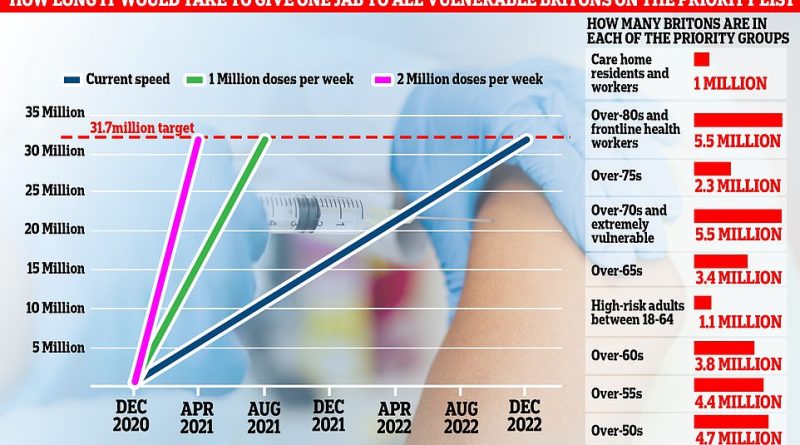

It comes after experts today warned that Britain may not be free of coronavirus restrictions until next winter unless the NHS hits its ambitious target of vaccinating 2million people every week.

In his televised address this evening, the Prime Minister said there was ‘one huge difference’ compared to last year: ‘We’re now rolling out the biggest vaccination programme in our history.’

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has laid out his best-case timetable to vaccinate all over-70s, frontline workers and vulnerable people by February but has urged caution over the timetable

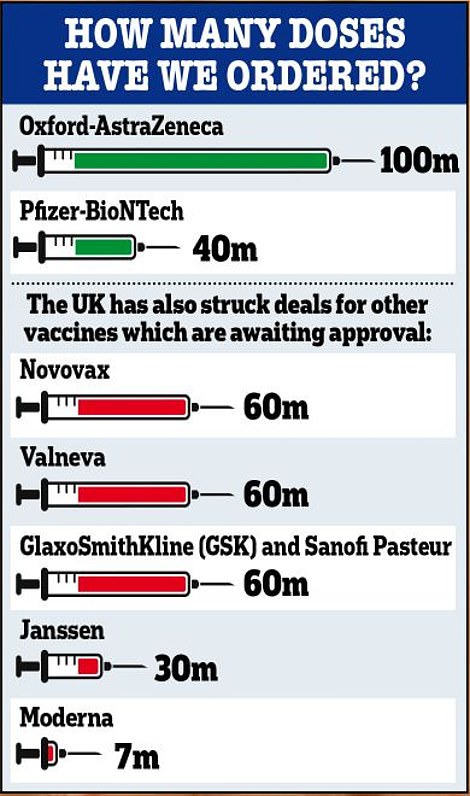

Prime Minister Boris Johnson watches as Jennifer Dumasi is injected with Oxford/AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccine during a visit to Chase Farm Hospital in north London earlier today

‘So far we in the UK have vaccinated more people than in the rest of Europe combined,’ he added.

He said the pace of vaccination was ‘accelerating’ with the arrival of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.

Mr Johnson outlined the NHS’s ‘realistic expectations’ for the vaccination programme in the coming weeks.

The Prime Minister said that meant all people over 70 and those with the most serious long-term health conditions are at ‘high risk’ from Covid.

Others in the high-priority group, which includes 14.3million people, are health and social care workers who could all be given a single dose each within seven weeks at the ambitious rate of 2million per week, so by mid-February.

‘If we succeed in vaccinating all those groups, we will have removed huge numbers of people from the path of the virus,’ the Prime Minister said.

‘And of course that will eventually enable us to lift many of the restrictions we’ve endured for so long.’

He added: ‘I must stress that even if we achieve this goal, there remains a time lag of two to three weeks from getting a jab to receiving immunity.

‘And there will be a further time lag before the pressure on the NHS is lifted. So we should remain cautious about the timetable ahead.

‘But if our understanding of the virus doesn’t change dramatically once again…

‘If the rollout of the vaccine programme continues to be successful…

‘If deaths start to fall as the vaccine takes effect…

‘And, critically, if everyone plays their part by following the rules…

‘Then I hope we can steadily move out of lockdown, reopening schools after the February half-term and starting, cautiously, to move regions down the tiers.

But Mr Johnson’s tentative pledge may fall flat, as the vaccine roll-out has not been free from hiccups so far.

Ramping up the inoculation drive to reach the target means it would still take until April for everyone over the age of 50, adults with serious illnesses, and millions of NHS and social care workers to get their first dose.

But it would take another 15 weeks for the same Britons to get the second dose they need to offer the

m as much protection against the disease as possible, meaning the deadline won’t be hit until August at the earliest.

Number 10 could, however, ease restrictions before then, if they believe they have protected enough of the population to prevent hospitals being overwhelmed.

But there are still huge questions about whether the NHS will be able to hit 2million jabs a week target, which scientists say Britain needs to get to ‘very quickly’ to have any hope of a normal summer.

AstraZeneca bosses have pledged to deliver the milestone figure of doses a week by mid-January. And the NHS has promised it will be able to dish them out as quickly as it gets them.

Brian Pinker, 82, became the first person ever to receive the Oxford University vaccine today

But there already appears to be cracks forming in the supply chain. Only 530,000 doses of the Oxford coronavirus vaccine will be available for vulnerable people this week, despite officials promising at least 4million just weeks ago.

Last week scientists blamed the vaccine’s slow roll-out on the government’s lack of investment and neglect of manufacturing.

Sir John Bell, a regius professor of medicine at Oxford University and member of SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies), said that insufficient investment in the capacity to make vaccines has left Britain unprepared.

He accused successive governments of failing to build onshore manufacturing capacity for medical products, with Oxford/AstraZeneca counting on outsourced companies to help create doses, such as Halix in the Netherlands, Cobra Biologics in Staffordshire and Oxford Biomedica.

After the vaccine is produced by those companies, it is transported to a plant based in Wrexham that is operated by an Indian company, Wockhardt, where it is either sent to another plant in Germany or transferred to vials.

England’s chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty has warned that vaccine availability issues will ‘remain the case for several months’ as firms struggle to keep up with global demand.

In a bid to ration supplies, the Government pledged to give single doses of the Pfizer vaccine to as many people as they can – rather than give a second dose to those already vaccinated.

Manufacturers of both the Pfizer and Oxford/AstraZeneca jabs have rubbished concerns, saying there is no problem with supply.

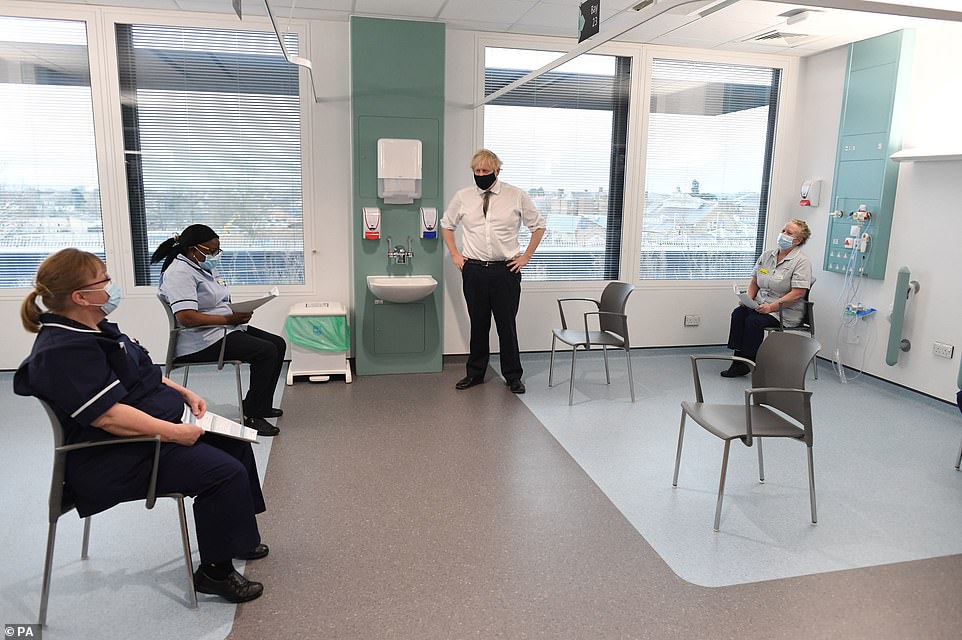

Trevor Cowlett, 88, receives the Oxford University/AstraZeneca Covid vaccine from nurse Sam Foster at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford as the NHS ramps up its vaccination programme

Sir Richard Sykes, who led a review of the Government’s Vaccines Taskforce in December, added that he is ‘not aware’ of a shortage in supply.

Meanwhile, the Government appeared to be trying to pass the buck for the vaccination programme before it has even had a chance to fail, with the Prime Minister saying the scheme was being stalled because officials were waiting for batches of the jab to be approved by the regulator.

The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) was the first in the world to approve both the Pfizer and the Oxford jabs — but it has stipulated that every batch of vaccine has to be individually inspected and quality controlled when it reaches the UK before being injected into Brits’ arms.

Wading into the row today, Dr June Raine, chief of the MHRA, dismissed the PM’s claim that the batch approval process was stalling the roll out and suggested it was issues further back in the supply chain.

Dr Raine said her team was ‘nimble and quick’ and could approve a batch in under 24 hours.

She told the BBC: ‘It’s a supply chain that goes right back from the manufacturer, right through to MHRA, and then on to the clinical bedside or where the vaccines are delivered, so we are a step on the road but our capacity is there, I’m very clear about that…

Boris Johnson speaks to NHS staff waiting to be vaccinated against coronavirus during a visit to Chase Farm Hospital earlier today ast he NHS is ramping up its vaccination programme

‘I was really proud last Wednesday when we approved the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, that we had approved the first batch the night before. We are that nimble and that quick.’

Matt Hancock also appeared to point the finger at AstraZeneca, the British drug firm responsible for making and distributing the Oxford jab, for the slow scale-up.

The Health Secretary insisted the NHS was ready to administer doses of the Oxford University vaccine as quickly as it received them, but he added: ‘The supply isn’t there yet’.

And Professor Stephen Powis, director of NHS England, added: ‘If we get two million per week, our aim is to get two million into pe

ople’s arms a week.’

The NHS today started to dish out Oxford/AstraZeneca’s game-changing Covid vaccine in what has been called a ‘pivotal moment’ in the fight against the pandemic, with an 82-year-old dialysis patient becoming the first person to receive the jab.

Brian Pinker, a retired maintenance manager who describes himself as Oxford born and bred, revealed he was ‘so pleased’ to get the vaccine and was ‘really proud’ it was developed in his city.

Mr Pinker is now looking forward to celebrating his 48th wedding anniversary next month with wife Shirley.

The UK’s vaccination programme has only managed to inoculate 1million people in the four weeks it has been operational.

But officials have promised the scheme will drastically speed up when clinics start using the game-changing Oxford University/AstraZeneca jab, which was rolled-out for the first time today.

Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease expert at the University of East Anglia, told MailOnline he would be ‘very surprised’ if ministers hadn’t eased some curbs by April, when millions will hopefully have been vaccinated.

He added: ‘I can see us having some sort of restrictions even this time next year.’

Professor Hunter said curbs would likely be a lot less severe and may depend on how many of the most vulnerable residents come forward for a vaccine.

If uptake is high, the virus has less room to spread and cause severe illness.

However, he said the only safe way to drop all restrictions would be to ensure enough of the population has become immune so that the virus fizzles out.

Scientists believe this can only achieved when 70 per cent of people are protected and the US’ top coronavirus doctor Anthony Fauci has warned the figure could even be as high as 90 per cent.

Government scientists have set the goal of 2million vaccinations per week because that will mean the most vulnerable third of the UK population will have some protection by Easter and can get their full two doses before autumn, before winter pressures will start affecting the NHS again.

At a pace of just 1million a week, it would take Britain 30 weeks to vaccinate all the vulnerable residents in phase one of the inoculation drive.

It means that they would not all get their second dose until next February and the health service could be faced with another winter crisis.

But Number 10 will not necessarily wait for the full cohort to be vaccinated before easing the cycle of restrictions.

Health Secretary Matt Hancock last month said that measures can be eased ‘when enough people who are vulnerable to Covid have been vaccinated then’. However, he never committed to an actual figure.

Experts say the number of vaccines Britain gives out before lockdown rules can start to be loosened will depend on the ‘risk appetite’ of Downing St and how well the jabs work in real life.

If measures are lifted too soon, then there could be a surge in severe cases, hospital admissions and deaths in groups at moderate risk but not priority for a vaccine, such as the middle-aged.

The NHS says that people over 70 and those with the most serious long-term health conditions are at ‘high risk’ from Covid.

These, combined with health and social care workers, make up a group of 14.3million people, who could be given a single dose each within seven weeks at the ambitious rate of 2million per week, so by mid-February.

But lifting lockdown rules by then would involve putting younger groups, such as those in their 60s, 50s and 40s, at risk from a then-uncontrollable v

irus.

And it would mean the people already vaccinated wouldn’t have the full protection of two doses, which both vaccines require.

This is why experts believe it is more likely that the UK’s restrictions will be phased out over a longer period to stop the virus spiralling among younger people, who still have a small risk of hospitalisation, death or long-term complications.

Dr Simon Clarke, a microbiologist at the University of Reading, told MailOnline last week: ‘It’s all very well vaccinating everybody over 65 and other people with long term health conditions, but the average of admission to intensive care is 60 and there are more men in their 40s in ICU with Covid than there are over-85s.’