Vaccine of freedom – or another fiasco in the making, asks DAVID ROSE

Just three days ago, Matt Hancock was basking in the glory of Oxford University’s astonishing achievement.

As its world-beating vaccine won approval from regulators, the Health Secretary toured the TV and radio studios, predicting that Britain’s coronavirus crisis would finally be over by Easter.

After all, ministers had ordered 100million doses of the ‘game-changer’ AstraZeneca vaccine, much more user-friendly than the Pfizer version already given to one million Britons.

And Alok Sharma, the Business Secretary, assured us way back in May that 30million doses would be on the shelves by September, ready for roll-out as soon as it had that crucial clearance.

More than that, an army of volunteers was – we were told – being recruited to take part in the biggest mass vaccination in British history.

Just three days ago, Matt Hancock was basking in the glory of Oxford University’s astonishing achievement. As its world-beating vaccine won approval from regulators, the Health Secretary toured the TV and radio studios, predicting that Britain’s coronavirus crisis would finally be over by Easter

They would complement the NHS, and quickly be able to deliver two million inoculations every week, starting with the most vulnerable.

As deaths and hospital admissions throughout the country spiralled horribly, this was, as the Prime Minister put it, our ‘beacon of hope’, our passport out of tiers and of lockdown, and of us starting to be able to live again.

After Government fiascos over personal protection equipment and a failed test and trace system, this was to be their shot at redemption. At last, in the dying days of the most terrible year, there was real hope that 2021 would be so much better.

Except, almost as soon as the initial euphoria had died down, nagging doubts began to emerge. Far from having millions of doses of the vaccine ready to roll-out, it has emerged that there are just 530,000 ready for the programme to begin on Monday.

Professor Chris Whitty, chief medical officer, admitted in an astonishing letter to doctors that, in fact, we are already facing vaccine shortages. Moreover, he said, they were likely to last for months.

And so the country’s medical experts signalled a sudden change in approach. The emphasis – which had been on inoculating the most vulnerable twice, with the doses separated by three weeks – was now to be on giving as many people as possible the initial dose.

Ministers ordered 100million doses of the ‘game-changer’ AstraZeneca vaccine, much more user-friendly than the Pfizer version already given to one million Britons… but far from having millions of doses of the vaccine ready to roll out, it has emerged that there are just 530,000 ready for the programme to begin on Monday

People would still get a second jab, but up to 12 weeks later. Elderly and vulnerable people inoculated once were told the appointments for their second dose were being cancelled.

And instead of a vaccination army ready to help the biggest inoculation drive in British history, it emerged volunteers were caught up in red-tape. Even retired doctors and nurses looking to help out face a mind-boggling list of 21 hurdles to clear.

So are these simply teething problems, or something more fundamental? And where does it leave the ambition of two million vaccines a week and freedom by Easter?

What has happened to supplies?

For months the Government has been boasting of its close relationship with Oxford and AstraZeneca, and how, when the time came, this would ensure a smooth vaccine roll-out.

Yet this week, asked why our current stocks are so unexpectedly low, Government sources were advising journalists they should ‘ask AstraZeneca’. There had been rumours of problems with glass phials, which were denied. There were some limited admissions from sources close to the company about batch control.

Compare us with India, where the Oxford jab is being made under licence. There are already at least 50million doses stockpiled at a giant factory in Pune, ready to go. Britain has less than 1 per cent of that to roll-out on Monday.

Last night one senior medical source, a viral vaccines expert who has been advising the Government, suggested the reason is the ‘messy data’ from Oxford’s clinical trials.

These suggested that giving an initial half-dose, followed by a full one four weeks later, was more effective than two full doses – a finding that emerged when trial participants were given the low dose by mistake.

Asked why our current stocks are so unexpectedly low, Government sources were advising journalists they should ‘ask AstraZeneca’. Above, a volunteer is administered the coronavirus vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and Oxford University

‘They didn’t go all-out to get in supplies for the start of the year because getting approval was taking longer than it did for Pfizer,’ the source said.

Another reason for the delay is that the Oxford vaccine needs to spend 20 days in sterilisation before it can be used, while each new batch has to be checked by regulators.

But Professor Adam Finn of Bristol University, a member of the Government’s official Joint Committee on Vaccines and Immunisation (JCVI), insisted the picture was less gloomy than it might seem.

There was, he said, ‘an overwhelming argument’ in favour of widening the dosage gap to protect more people sooner, even though this was a result of shortages.

He added: ‘The UK is actually doing alright compared to other places. There are difficulties in rolling the vaccines out – but something as complicated as this has never been done before.

‘I’m personally impressed we’ve already managed to vaccinate 900,000 people – and now the use of the Oxford vaccine is going to make it much easier to target the elderly.’

Is lengthening time between doses bad?

Some experts believe that lengthening the gap between first and second dose from three to 12 weeks may actually improve protection, at least in the case of the Oxford vaccine.

But Pfizer has signalled it is unhappy its vaccine will be used in Britain in a way never envisaged when it passed its clinical trials.

Professor Whitty explained the controversial change in his letter to doctors: ‘For every 1,000 people boosted with a second dose of Covid-19 vaccine in January, 1,000 people can’t have substantial initial protection, which is in most cases likely to raise them from 0 per cent protected to at least 70 per cent protected.’

He continued: ‘These unvaccinated people are far more likely to end up severely ill, hospitalised and in some cases dying without the vaccine.’ In other words, in a cost-benefit analysis, opting for the new approach means more people are protected.

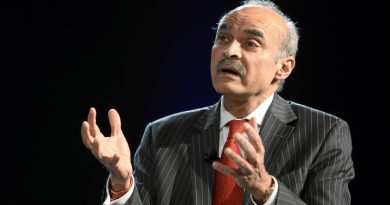

Professor Chris Whitty, chief medical officer, admitted in an astonishing letter to doctors that, in fact, we are already facing vaccine shortages. Moreover, he said, they were likely to last for months

But could it be risky?

Professor Finn said with the Pfizer vaccine, people who got their first jab would soon have 91 per cent protection. That figure would rise only marginally to 95 per cent after their second.

‘Vaccines going into more arms will save more lives’, he said.

According to the official committee on which he sits, data shows that the American Moderna vaccine – approved for use in the US, but not yet in Britain – is very similar to the Pfizer jab. It seems to grant protection from a single dose for at least 15 weeks – and it is this that the JCVI have used in coming to the decision about the Pfizer jab.

Yet Deenan Pillay, professor of virology at University College London, and a leading member of the UK Virologists’ Network, said there was a ‘theoretical possibility’ that delays in giving a second dose might encourage new mutations. He said: ‘Of course, I see there the argument that if you maximise the numbers who get an initial dose, that will be beneficial. But there is a theoretical risk.’

Professor Finn dismissed this. ‘This kind of speculation is not helpful. But we need to be astute about the mutations that do occur and whether they mean we need to alter the vaccine.’

What about those waiting for 2nd dose?

Joan Bakewell, the broadcaster, was overjoyed to get her first jab three weeks ago, and had been scheduled to complete her treatment next week. She was looking forward to dinner with a friend later this month, and resuming her life. Now she is now left in limbo.

Mrs Bakewell, 87, writes in the Mail today: ‘I’ve heard nothing from my GP or clinic, and have no idea if my life will go back to normal at the end of this month, or not until the end of March. Until I do, nothing is certain.’

The British Medical Association says it believes that ‘existing commitments’ to give a second jab to patients who have already had their first ‘should be respected, and if GPs decide to honour these booked appointments in January, the BMA will support them’.

Richard Vautrey, head of the BMA’s GP committee, said not meeting this would be ‘grossly unfair to tens of thousands of our most at risk patients.’

Vinesh Patel, of the Doctors’ Association UK, urged the Government to think again: ‘A patient can’t consent for a treatment then have it changed without their permission, especially when the evidence for change is lacking.’

Where is the army of vaccinators?

Many GPs have been saying for weeks they are already too busy to shoulder the burden of immunising millions – and ministers had a plan, apparently.

Recruiting a volunteer army was to be key in helping deliver its two million doses a week – and much more so now hospitals are again overwhelmed as the second wave of the virus comes close to the levels experienced in April.

There has been talk of this new force of ten thousand or more for months, yet even retired health professionals – as the Daily Mail revealed yesterday – are facing inexplicable bureaucratic hurdles against joining it, such as providing evidence of their diversity and human rights training.

Nicola Thomas, a professor of kidney care at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, said: ‘To be asked for proof of address, two references and additional e-learning, including fire safety is really too much to bear.’

Michael Marshall, chairman of the Royal College of General Practitioners, said: ‘Some of these bureaucratic demands are ridiculous, such as the requirement to be certified in ‘fire safety’, ‘conflict resolution’ and ‘preventing radicalisation’.’

The signs yesterday were that these restrictions will be eased – but quite how is yet to be explained.

And yesterday, a new problem emerged: not only a shortage of civilian vaccinators, but a shortage of people qualified to interview them for the job – a process which may add a further delay of weeks.

Will we still escape all this by Easter?

Buffeted by so many aspects of the crisis, perhaps it’s not surprising senior Government sources reacted with deep hostility to questions about the target of normal life by Easter.

One source close to the Health Secretary even suggested this newspaper’s attempts to subject them to scrutiny suggested we were somehow ‘anti-vaccination’ – when the very opposite is true. As our editorials have made clear, the Mail is certain that vaccination is indeed the pathway to normality.

The suggestion is that there were robust answers to all of this. Trouble is, they are failing to deliver them convincingly.

Mr Hancock said of the one million vaccinations being reached: ‘It is fantastic that we have reached this milestone, and we continue to accelerate the vaccine roll-out.’

It is understood there are four million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine now being prepared and checked, and still awaiting clearance. So there is room for some optimism. As for the roll-out, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace says the Army is ready to administer 750,000 vaccines a week.

But the stakes could hardly be higher. While the public tolerated PPE scandals and failures on test and trace, another fiasco on vaccines may be a failure too far.