Has the riddle of Britain's true-life X-File finally been solved?

Two nights after Christmas, 1980, and the American servicemen of Combat Support Group were letting off steam in the early hours at Woody’s Bar.

An awards dinner was still in full swing and beer was flowing in the hut at RAF Woodbridge in Suffolk.

No one paid much attention to the white-faced young airman who slipped into the bar and beckoned to his commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Halt.

Halt left the table. The junior officer, Lieutenant Bruce Englund, looked nervous and confused: ‘It’s back, sir,’ he said over the hubbub. ‘The UFO — it’s back.’

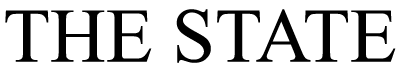

A Vietnam veteran and deputy commander of the camp, Halt was exasperated. Rumours of a bizarre sighting in the woods had been rife on the twin bases at RAF Woodbridge and RAF Bentwaters, near Ipswich, which were shared with the U.S. Air Force.

The men were so puzzled that they didn’t think to alert the emergency services. They simply walked deeper into the woods, slowly and warily, like actors in a science-fiction movie

The first he’d heard of it was when he came on duty at 5am on December 27: he walked into his office to hear loud chatter and laughter that stopped abruptly as he entered.

‘What’s going on?’ the 41-year-old Halt snapped. A sergeant answered, with a mixture of embarrassment and bravado: ‘Penniston and Burroughs were out last night chasing UFOs, sir.’

Conflicting gossip and tall stories spread all day across the camp. Halt tried not to waste time on them, though protocol demanded that reports were filed.

The excitement was already half-forgotten by that evening . . . and then Lt Englund barged into Woody’s Bar.

Halt left the bar to investigate. What he saw changed his life, and everything he thought he knew about the world, for ever.

In Rendlesham Forest, beyond the camp’s perimeter, the war-hardened Air Force colonel witnessed something that could not possibly be of earthly origin — and he was willing to stake his entire military reputation on that fact.

‘I believe the objects that I saw at close quarter,’ he later swore in an affidavit, ‘were extraterrestrial in origin, and that the security services of both the United States and the United Kingdom have attempted — both then and now — to subvert the significance of what occurred.’

This was the beginning of the case dubbed Britain’s Roswell: an encounter with apparently alien technology so extraordinary that no attempt by sceptics to dismiss it has been able to explain away all the basic facts of the story.

The Rendlesham Forest incident began 40 years ago in the early hours of December 26, 1980, as most of Britain was sleeping off the effects of Christmas Day.

Rumours of a bizarre sighting in the woods had been rife on the twin bases at RAF Woodbridge and RAF Bentwaters, near Ipswich, which were shared with the U.S. Air Force

Airman First Class John Burroughs was on patrol close to the East Gate at Woodbridge when he saw flashing red and blue lights, shining from the direction of the East Anglian coastline.

Burroughs had been standing guard at the camp for 17 months and had never seen anything like this. His first thought was that a light aircraft had come down in the trees.

He alerted his sergeant, Bud Steffens, and the two men reported their concerns before they were joined by another sergeant, Jim Penniston, and his driver, Airman First Class Edward Cabansag.

While Steffens stayed on duty at the gate, the other three took a Jeep into the woods. After about 250 yards, the track petered off and they got out to walk. By now, the lights seemed brighter and more varied — not only red and blue, but white and yellow.

There seemed to be no flames or any other indication of a crash, though. The men were so puzzled that they didn’t think to alert the emergency services. They simply walked deeper into the woods, slowly and warily, like actors in a science-fiction movie. A fourth man, Master Sergeant J.D. Chandler, caught up and joined them.

And then all four of the men’s radios started to malfunction.

Realising they were cut off from their base, the men backtracked. The found they could still get a signal to the camp from where they had left the vehicle, so Chandler volunteered to stay there.

The others went forward, until they began to lose touch with Chandler. Cabansag agreed to hold back too, as a one-man radio relay station, while Burroughs and Penniston kept going.

Now the atmosphere in the forest had become strange and frightening. Static electricity made the men’s hair bristle. Walking became heavy and difficult, as if they were wading through water.

As they approached a clearing, there was an explosion of light. Both men threw themselves to the ground. Burroughs looked up and saw Penniston, silhouetted by the red glow of an object in the open ground.

‘The silence was then the most prominent part of it,’ Burroughs reported. ‘The area or field seemed dead. The air: no sound. No rustling of air or wind, no distant sounds, no animals or nothing.

‘A dead silence. A strong static on clothes, hair and skin, being pulled towards the light. Then dissipated.’ But Penniston’s memory of the events was utterly different.

As the blast of light engulfed him, he saw beyond it a small metallic craft, about 10 ft across and 10 ft high. Roughl

y triangular, it appeared to be either standing on the ground or hovering just above it.

Dazed, Penniston walked closer. The hull of the object was dark and smooth, and incised with hieroglyphs. He ran a hand over the surface.

‘The skin of the craft was smooth to touch,’ he said. ‘Almost like running your hand over glass. Void of seams or imperfections, until I ran my fingers over the symbols. The symbols were nothing like the rest of the craft — they were rough, like running my fingers over sandpaper.’

Light began to glow at the top of the craft and it lifted off slowly . . . then shot up into the sky and disappeared at what Penniston called ‘impossible speed’.

The Rendlesham Forest incident began 40 years ago in the early hours of December 26, 1980, as most of Britain was sleeping off the effects of Christmas Day

Afterwards, it seemed to him that he had studied the object for several minutes — not the handful of seconds that Burroughs perceived passing. Both men were staggered to be told later that they had been out of contact for 45 minutes. More incredible still, both their wristwatches were now three-quarters of an hour slow.

This was the story going round the camp later that day, causing hilarity and incredulity.

In daylight, Burroughs and Penniston took a team of U.S. Air Force investigators to the site and found indentations in the ground, broken branches and scorch marks on the trees.

When the lights returned in the early hours of December 28, Halt took six men to investigate. Among them were Lt Englund and Airman Burroughs. He also took a cassette recorder, which he used to record the team’s discussions at the site, and a Geiger counter to detect radiation.

The dark woods were ‘strange’ and ‘eerie’, in Halt’s words.

His unease was heightened when farm animals began to bleat and grunt in the distance, and something in the darkness started to make sharp, shrieking sounds — possibly a wild muntjac deer.

Then the lights began — beams from airborne objects, ‘strobe-like flashes’ in the words recorded on Halt’s cassette, ‘shooting off’ so bright that ‘it almost burns your eye’. Then a pencil-thin beam hit the ground in front of him.

‘We just stood there in awe,’ he said later. ‘Is this a warning, is this a signal, is this a communication? What is this? A weapon?’

Just as on the first night, a burning red oval light materialised. ‘It reminded me of an eye,’ Halt said, ‘and appeared as though blinking. It manoeuvred horizontally through the trees with occasional vertical movement. When approached, it receded.’

Then the woods exploded in light once more. This time it was Airman Burroughs who felt himself drawn into it, for what seemed like a matter of seconds — though his companions testified he was gone for several minutes.

‘I have no recall of it,’ he says now. ‘I have no memory of what happened.’ The team retreated. By the time they were out of the woods and in a meadow (where Burroughs regained his memory), they could see the red oval in the sky.

It seemed to be dropping blobs of light like molten metal over the air bases, before breaking up into multiple smaller white lights and dispersing in all directions.

‘I have no idea what we saw,’ Halt said, ‘but I do know whatever we saw was under intelligent control.’

For the next 40 years, UFO believers and sceptics would argue furiously about what happened on those two nights.

The details did not become public at once, but leaked out slowly.

In October 1983, the now-defunct News Of The World tabloid obtained a copy of Halt’s report and published extracts on its front page under the headline, ‘UFO Lands In Suffolk — And That’s Official’.

Two years later, a sceptical Guardian journalist investigated and concluded that what the airmen had seen must have been the beam of the Orfordness lighthouse, five miles away. Seen from one angle, the light appears to track through the trees, winking at just above ground level. The lighthouse also has two red lights mounted on aerials.

According to this theory, the depressions left in the ground by the UFO’s tripod feet were in reality rabbit holes, and the scorch marks on trees were left by foresters.

The malfunctioning radios were put down to ordinary equipment failure and everything else was delusion caused by fear and over-active imaginations.

There is also the suggestive fact that a post-Christmas celebration was going on in Woody’s Bar before the second expedition. Alcohol might have been a factor in the sightings and the way they were interpreted.

Other sceptical explanations include collective hallucinations caused by psychotropic drugs which (according to one truly outlandish conspiracy theory) were being administered to personnel at the air bases without their knowledge or consent.

More credible is the suggestion that the lights which Colonel Halt interpreted as ‘molten metal’ falling from the sky were created by a meteor shower.

But none of this explains the radiation readings on the Geiger counter — which have led some amateur investigators to theorise that there could have been an accident involving a nuclear weapon at the base. That would certainly explain the flash of light, though not why all who saw it survived.

A more feasible, though still highly speculative, theory was floated by ufologist Nick Redfern last year in a book called The Rendlesham Forest UFO Conspiracy. Redfern suggests that the U.S. military was experimenting with ways to harness ball lightning, a natural phenomenon, as a weapon.

Two years later, a sceptical Guardian journalist investigated and concluded that what the airmen had seen must have been the beam of the Orfordness lighthouse, five miles away. Seen from one angle, the light appears to track through the trees, winking at just above ground level. The lighthouse also has two red lights mounted on aerials

The idea of bottled lightning was first investigated by Cold War scientists in the 1950s.

Sometimes this was sheer sci-fi scaremongering: a journalist named D.V. Ritchie published a piece in Missiles And Rockets magazine in 1959, headlined, ‘Reds May Use Lightning As A Weapon’.

Other studies had a more serious academic basis. Using a Freedom of Information request, Redfern obtained a document by two scientists called Lyttle and Wilson, who were employed by a military technology company called Melpar Inc, which was listed as ‘an American government contractor in the 20th century Cold War period’.

Their paper was titled ‘Survey of Kugelblitz theories for electromagnetic incendiaries’. Kugelblitz is German for ball lightning, a sort of levitating ball of fire.

Lyttle and Wilson proposed that if white-hot ball lightning could be generated artificially, laser beams might be used to guide it to targets. Colonel Halt reported seeing pencil-thin beams radiating down from the blinking red oval — could these have been lasers, Redfern wonders?

But perhaps the most entertaining explanation was uncovered by UFO enthusiast Dr David Clarke, after he received a letter from a former SAS trooper three years ago.

Though the government refused to acknowledge the fact at the time, in 1980 RAF Woodbridge was a nuclear site. If the public didn’t know that American warheads were situated there, Soviet intelligence certainly did. The threat that enemy spies might penetrate the base was ever present.

To test the vulnerabilities, British special forces made repeated forays into the camp, demonstrating where the weaknesses were in its fortifications. One night, in August 1980, an SAS team performed a daring free fall from a high-altitude plane over Suffolk at night. Their black parachutes were designed to be invisible to the watchers below.

But the American radar equipment was more sensitive than the British had guessed. As the SAS men touched down inside the Woodbridge perimeter, they were arrested and dragged away for interrogation.

So far, so routine. This was meant to be an ordinary exercise, and both sides were carrying out orders. But then it went wrong.

One night, in August 1980, an SAS team performed a daring free fall from a high-altitude plane over Suffolk at night. Their black parachutes were designed to be invisible to the watchers below. But the American radar equipment was more sensitive than the British had guessed

The Americans reacted with unexpected aggression — subjecting the intruders to a brutal beating and 18 hours of questioning. Refusing to believe the parachutists were British military, they repeatedly accused them of being ‘aliens’.

The SAS men were not freed until the Ministry of Defence in London demanded their release.

As one special forces trooper, calling himself Frank, told Dr Clarke: ‘They called us aliens. Right, we thought, we’ll show them what aliens really look like.’

In an elaborate prank, the unit rigged coloured lights and flares around the forest. Black helium balloons were attached to radio-controlled kites and sent buzzing over the treetops.

In the days after Christmas, when the SAS rightly guessed that the mood inside the base might be more relaxed and susceptible, the elaborate jape was triggered.

It proved more effective than the troopers could ever have expected. They hoped to spook a few naive U.S. airmen, jittery at being alone in the ancient woods. In fact, they convinced a Lieutenant Colonel that he was experiencing a ‘close encounter of the third kind’.

Even the MoD took the reports seriously at first. But it wasn’t long before someone in London remembered that Woodbridge was the scene of the previous summer’s embarrassment, when an SAS unit was captured and labelled ‘aliens’.

The connection was made. Frank and his friends were ‘spoken to’. They admitted they might have indulged in a bit of a joke. Was it their fault if the Americans were so gullible?

Still, the investigation was thorough, and reports went all the way to the top. In 1985, Defence Minister Lord Trefgarne had an off-the-record meeting with Lord Hill-Norton, a former chief of the defence staff, to discuss the incident.

In his briefing notes, the phrase ‘no additional action required’ is used. And in handwriting on the margin, Trefgarne has written, ‘Oh dear’.