Nilambur Ayisha: India actor who survived religious hate and bullets

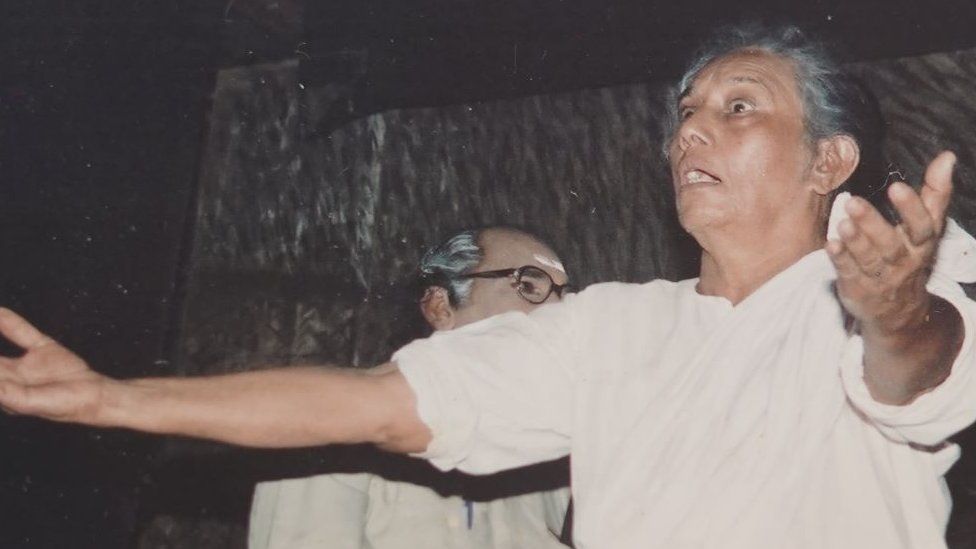

The year was 1953. Nilambur Ayisha, 18, was on stage delivering a dialogue when a bullet whizzed through the air.

“It missed me and hit the stage curtains because I moved while speaking,” recalls Ayisha, now 87, sitting at her home in the town of Nilambur (which became part of her stage name) in the southern Indian state of Kerala.

The shooter’s attempt was just one among several – by religious conservatives who believed a Muslim woman shouldn’t act – to force Ayisha off the stage.

But she went on acting, braving sticks, stones and slaps until, she says, “we managed to change people’s attitudes”.

Last month, Ayisha was in the front row when a new generation of actors in Kerala presented a reimagined version of the play she was doing when she was fired at – Ijju Nalloru Mansanakan Nokku (You try to become a good human being).

The new version opens with the shooting attempt at Ayisha and takes aim at religious conservatism among Muslims, much like the earlier version – except that it incorporates several recent incidents of intolerance and religious dogma, especially those intended to oppress women.

For instance, a few weeks ago, a senior Muslim leader in Kerala kicked up a controversy after scolding the organizers of an event for calling a female student to receive an award on a stage.

Since 2014, when the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party swept to power in India, attacks on Muslims – the country’s largest minority at 200 million – have risen sharply.

In turn, the minority community is also going through a political churn where moderate voices are finding it harder to counter what is sometimes an assertion of conservative practices in the name of championing religious identity.

Ayisha says she is worried that the conservatism she and her fellow artistes – many of them Communists – fought against in the 1950s and 60s is deepening in India, including in Kerala, often called one of India’s most progressive states.

“We tried to change these attitudes earlier. But now, when there is objection to a young girl going up on stage, it feels like we are going back to those dreadful days,” she says.

It began with a gramophone

Ayisha was born in a rich family which fell on hard times after her father’s death. They received, she says, little help from community leaders when they struggled to survive.

Life was difficult, but she was happy to be at home. She had left briefly some years ago – when she was just 14, she was married off to a 47-year-old man, but walked out of the marriage after just four days. She realised later that she was pregnant but went ahead with divorcing him.

One day, she was singing along to a record on the gramophone – “the only item of luxury left in our house” – when her brother and his friend, playwright EK Ayamu, walked in.

At the time, a progressive theatre group backed by Communists was gaining ground in the state with dramas, fiery political songs and other forms of art. It inspired several smaller groups to attempt writing and staging plays.

But most of the roles – including those of women – were played by men.

When EMS Namboodiripad – who in 1957 became India’s first Communist chief minister when a government headed by him came to power in Kerala – watched one of these plays, he suggested to Ayamu that they find women to act in roles written for them.

When Ayamu heard Ayisha sing, he asked if she would play the challenging part of Jameela, a housewife who had a pivotal role in the drama.

Ayisha was ready, but her mother was worried that they would be ostracised by religious leaders.

“I told her that they never came to our rescue when we were in trouble. So how can they punish us now?” Ayisha says.

The play was a huge hit, but it also ruffled many feathers.

“There were a lot of attacks on us. Muslim conservatives found it blasphemous that a woman from the community was appearing on stage,” says VT Gopalakrishnan, who played the son of Ayisha’s character in the drama.

People threw stones at Ayisha when she was acting; her colleagues were attacked when they tried to protect her.

Once, a man jumped on the stage and slapped Ayisha so hard he damaged her eardrum – it left her with a permanent hearing disability. The man who shot at her was never caught.

Did these attacks scare her?

“Not at all. My strength only increased,” Ayisha says.

“It was a humane drama about bringing out the good in people and loving others regardless of their backgrounds. That is also why our troupe was targeted so many times,” she says.

Ayisha’s courage under fire has given her an undeniable place in Kerala’s history, says Johnny OK, a senior journalist.

“She was part of the social reformation movement that made a difference through art and culture,” he says.

Ayisha went on to act in several plays and films, but after a while, offers began drying up.

She then went to Saudi Arabia to work as a domestic helper “for how long, I can’t remember”.

When she returned to Kerala, she began acting again in Malayalam-language movies, winning awards for some of her performances. She is also invited to speak at workshops and programmes where many cite her as an inspiration.

Looking back, she says she has no regrets.

“I withstood everything, including the physical attacks. Today, at the age of 87, I can proudly stand before the world.”