CIA’s 1960s experiments to create ‘remote control’ dogs by implanting electrodes into their brains

Documents of the CIA’s 1960s ‘remote controlled’ dog experiments were declassified in 2018, but images of the canines fitted with electrodes in their brains have recently emerged.

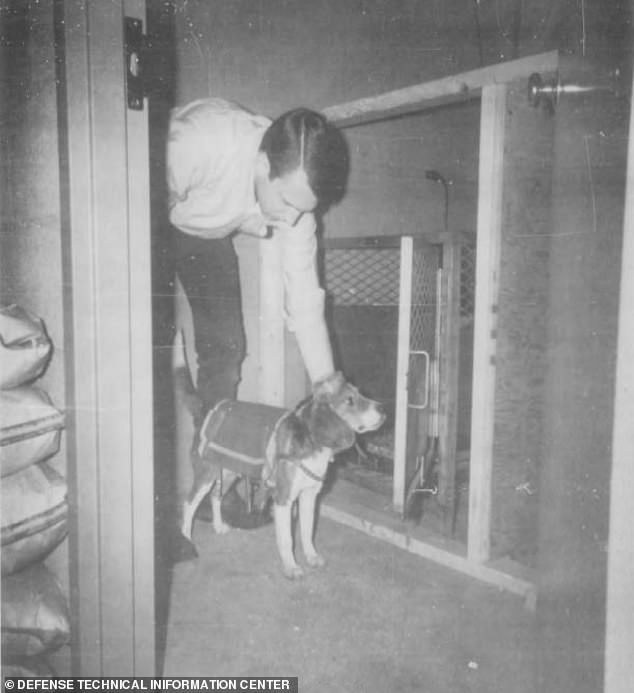

The black-and-white photos show beagles strapped with a receiver-stimulator on their back and a protective helmet covering where the devices were surgically placed in their skulls.

The newly declassified documents also describe three tests subjects in the program that endured shocks up to 90 volts, with one being zapped 2,000 times until it began convulsing and died.

The research setout to determine if it is feasible to control them through brain-stimulation reward, but it is not known if any of the surviving dogs were used in military missions.

The top secret experiments were part of the infamous mind control project MKUltra, which conducted hundreds of experiments sometimes on unwitting citizens to assess the potential use of LSD.

Documents of the CIA’s 1960s ‘remote controlled’ dog experiments were declassified in 2018, but images of the canines fitted with electrodes have recently emerged. The black-and-white photos show beagles strapped with a receiver-stimulator on their back and a protective helmet

US officials tried to hide the top secret ‘behavior modification’ files for decades, but were forced to release the documents to the public under the country’s Freedom of Information laws.

‘The specific aim of the research program was to examine the feasibility of controlling the behavior of a dog, in an open field, by means of remotely stimulated electrical stimulation of the brain,’ one of the documents state.

‘Such a system depends for its effectiveness on two properties of electrical stimulation delivered to certain deep lying structures of the dog brain: the well-known reward effect, and a tendency for such stimulation to initiate and maintain locomotion in a direction which is accompanied by the continued delivery of stimulation.’

John Greenewald, creator of The Black Vault, petitioned the Department of Defense in July 2020 to release one of the classified documents titled: ‘Some Behavioral Correlates of Brain-Stimulation Reward: Part B.’

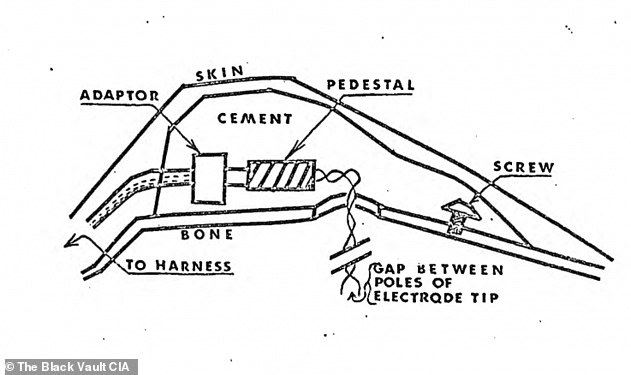

Scientists at first used a plastic helmet (schematic pictured) that delivered the stimulation to the dog’s brain but then moved on to embedding the electrode within a mound of dental cement into the skull

The newly declassified documents also describes three tests subjects in the program that endured shocks up to 90 volts, with one being zapped 2,000 times until it began convulsing and died

This report describes the process dogs endured through the experiment – from surgery to the field for tests. According to the document, the CIA started this work in rats and monkeys, and following successful experiments the agency moved to dogs

This report describes the process dogs endured through the experiment – from surgery to the field for tests.

According to the document, the CIA started this work in rats and monkeys, and following successful experiments the agency moved to dogs – specifically beagles.

The researchers first tried out a plastic helmet but then settled on a new surgical technique that involved ’embedding the electrode entirely within a mound of dental cement on the skull’, the documents state.

‘The dog’s skull was roughed up with the drill in order to provide ‘grips’ for the dental cement.’

‘In addition to roughing up the skull, we drilled a number of small holes into, but not through, the skull.

They ran the leads just below the dog’s skin to a point between the shoulder blades, where the leads are brought to the surface and affixed to a standard dog harness

The canine test setout to determine if it is feasible to control them through brain-stimulation reward, but it is not known if any of the surviving dogs were used in military missions

They ran the leads just below the dog’s skin to a point between the shoulder blades, where the leads are brought to the surface and affixed to a standard dog harness.

After the electrodes were implanted, personal would deliver about 80 to 90 volts of electricity to simulate the dog’s behavior by having it press on a lever.

‘After about 2000 ‘fast’ responses, convulsions developed of sufficient severity to kill the dog,’ the document states regarding one of the beagles.

Following the dog’s death, researchers moved on with their work using to another beagle they named Eureka.

Unlike the previous, personnel started out with about 12 to 15 volts over the course of a few days.

After testing concluded, Eureka showed no signs of deterioration in its performance.

‘A question arose: should we continue to work with Eureka I or should we sacrifice him for histological analysis? We decided on the later course,’ reads the report.

‘Histology has just been completed on that dog, and our judgement is that the electrode tip was in the media forebrain area, perhaps in the Campi Foreli.

Following this loss, Eureka II was brought onboard for experiments and upon showing positive results in the field he was brought indoors for an endurance test.

The dog was kept in an experimental box for a continuous eight hours, while being shocked to see how many times he could press a lever – it is not stated what became of Eureka II.