Numbers won’t tell us when the pandemic is over

Courtney Gidengil has a roadmap for how the COVID-19 pandemic might end. It was sketched out the last time the United States transitioned out of a pandemic — the “swine flu” outbreaks in 2009.

Gidengil, a senior physician policy researcher at the RAND Corporation, spent that pandemic asking a group of adults how worried they were about the virus. Their answers changed through the course of her eight-month study. Early on, people were worried that they’d get sick, and that if they got sick, they’d die. Then, as we learned more about the virus, a flu strain called H1N1, they felt like they were less at risk. The virus was still around, but people weren’t as scared of it. Eventually, it just became one of the normal flu strains that circulate each year.

“We understand more about it, but people also just become attuned to the risk,” Gidengil says. ”It just becomes more like background noise in everyday life.”

That emotional transition — from fear and uncertainty to gradual acclimatization — is likely to happen again with COVID-19. H1N1 is a very different disease than COVID-19; it was far less deadly and barely disrupted most people’s day-to-day lives. But it’s one way to picture what the social trajectory out of a pandemic can look like.

Right now, COVID-19 is still killing people all over the world — the pandemic is still viscerally real. But in the US, it doesn’t have the same sharp bite as it did six months ago. The end feels close: case rates have been falling for weeks, and tens of thousands of people get vaccinated each day. The virus is being beaten back unevenly all over the world, but populations will each adjust to living with the new disease as the risk of it becomes more and more tolerable — it won’t feel like it’s an emergency anymore. It’ll just be another virus that sometimes makes people sick.

That gradual adjustment is partly why the end of the pandemic feels so slippery: there’s no one number of cases to reach or switch that will flip to mark the end. We’re not waiting for a group like the World Health Organization to say it’s over, and even if it did, that announcement wouldn’t be essential — after all, some people started calling the outbreak a pandemic before the WHO did. In many ways, COVID-19 will stop being a pandemic disease and start being a regular disease when we feel like it has. The end will be based on people’s tolerance for risk, personal values, and straight vibes — not a hard-and-fast data point. And that transition will be different for everyone.

“We will be very attentive to the coronavirus for a while, and then it will enter the kind of background welter of things that kill us,” says Nicholas Christakis, a sociologist and director of the Human Nature Lab at Yale University. “Slowly, we will stop paying attention to it — that will define the social end of the pandemic.”

A regular threat

We probably won’t be able to get rid of COVID-19 entirely. Vaccination, improved treatments, and familiarity with the virus will defang the threat. Already, it looks like vaccinating the people at the highest risk from dying of COVID-19 has brought down its overall fatality rate in the United States. But the virus will continue to circulate through the population, and eventually, the peaks and valleys of the pandemic will settle at some sort of consistent height. At that point, it will have transitioned from a pandemic disease — an illness that spreads rapidly and affects the entire world — to an endemic disease.

Those are specific, technical terms, but in many ways, their definitions are based on experience and emotion. Pandemic diseases are unpredictable and cause unexpected, scary amounts of death and sickness. Endemic diseases, on the other hand, are predictable. They’re a threat but a threat the population is used to. Think: seasonal flu, chicken pox, some sexually transmitted diseases, malaria in parts of Africa.

“When you shift from pandemic to endemic, it means that there’s a collective acceptance that we are now living with this disease,” Gidengil says.

Personally, I’ve spent a lot of time lately wondering what that acceptance will look like for me. I’m fully vaccinated, and so are most of my friends and family. I’ve started to ease back into “normal” activities like visiting my parents, browsing clothing stores, and making dinner with friends. But it still feels weird to take off my mask inside if there are strangers around. I still jump when someone coughs nearby. Hearing someone I know has COVID-19 would still be scary. Logically, I know my risk from COVID-19 is many times lower than it was a month ago — but that’s hard to internalize after over a year of fear.

The adjustment to living with COVID-19 as a background threat will be different for everyone, says Steven Taylor, clinical psychologist and author of The Psychology of Pandemics. People who had higher baseline levels of anxiety may take longer to adjust to a new relationship with the virus. “It’s going to be tough for some people to wrap their heads around the idea that the pandemic is over, but people are still getting sick and dying from COVID-19,” he says. On the other hand, people who normally cope well with stress will navigate the transition to having an endemic virus more easily.

It’s worth taking a second to talk about another slippery, complex part of this discussion. Some people never believed that COVID-19 posed much of a threat and went about their normal lives over the past year. At that point in time, deciding to tune out COVID-19 and think of it as just a background threat wasn’t reasonable. COVID-19 was still clearly and objectively a pandemic, with soaring cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. Decisions that just ignored reality were dangerous for individuals’ health, the health of others, and health systems overall. In some places in the world, COVID-19 is still a clear and present danger, and the end of the pandemic is still far away. But over 2021 and 2022, as vaccination rates go up and the levels of COVID-19 fall, the pandemic can start to become more subjective. Personal risk tolerance will play a bigger and bigger role in how people manage their relationship with the virus.

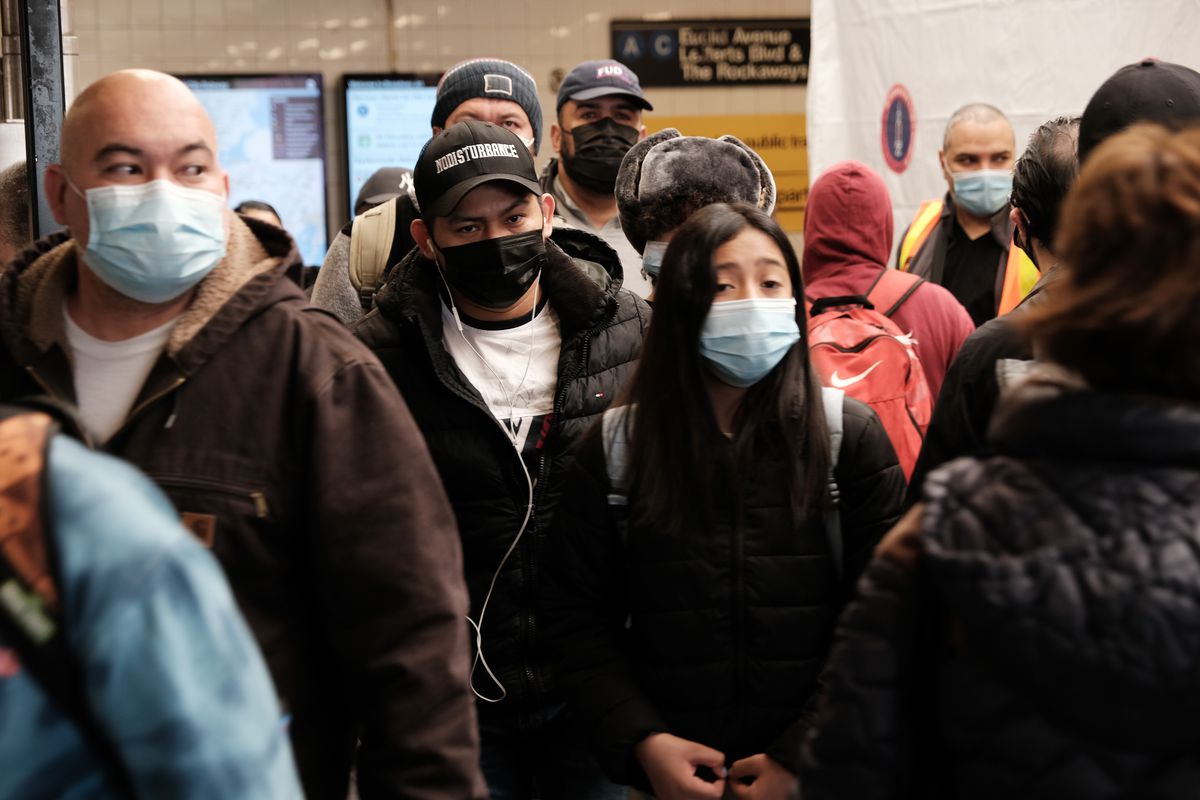

Photo by Spencer Platt / Getty Images

“When we get to a point where we have very low levels of hospitalizations and deaths, it’s less of a public health issue,” says Jennifer Nuzzo, an epidemiologist and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Then, we could start to see reasonable differences in how people navigate their changing relationship with COVID-19. Some people might still want to avoid any situations where they could be exposed to the coronavirus. Others might be willing to risk it for the chance to go to an indoor concert, for example.

Making that choice might feel similar to the choice to get into a car, even though there’s a high risk of an accident. “We look at the risk of getting into a car accident as worth it because of the value that transportation by motor vehicles brings to our lives,” Nuzzo says.

An uncertain timeline

There’s no playbook for how the adjustment period from pandemic to background, endemic threat will go or for how long it could take. Gidengil’s research showed that H1N1 stopped feeling like a pandemic over the course of a few months, but that virus was never as scary as COVID-19. HIV offers another example, Taylor says — it still circulates and is still dangerous, but when effective treatments were developed, the anxiety around it started to fade.

Even with treatments, though, that adjustment to HIV took years, says Yale sociologist Christakis. “People stopped thinking about it as much, but there wasn’t a rapid decline in the public consciousness.”

It’s still unclear how that will play out with COVID-19. The emergence of viral variants might make the adjustment process bumpier than the arc of H1N1 — while H1N1 faded quickly, new variants of the coronavirus might raise public concerns at uneven intervals.

As cases fall and vaccinations increase, policy changes may influence how people feel about the virus. Local and federal health agencies could decide to only report new COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths, rather than every single new case, Nuzzo says. That could signal to people that each individual case isn’t as much of a threat. Changes in mask mandates also give people cues. We’ve seen that recently with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s mask guidelines for people who are fully vaccinated. Telling people that they can stop wearing masks in certain situations indicates that they can start to let their guard down.

Still, policy doesn’t always dictate people’s relationships with COVID-19. In some areas, vaccinated people may be sticking to masks, even where the CDC and local regulations say they’re no longer necessary. “I think it’s ultimately going to matter how comfortable people feel,” Nuzzo says.

That comfort will come with time — and with familiarity. My brother had COVID-19 this spring. He recovered just fine, but he was undeniably sick for around a week — no appetite, a high fever, a horrible sore throat, unable to get out of bed. He’s young, and he was never in any serious danger, but it was still scary.

If a family member got sick a year from now, Taylor thinks I probably wouldn’t be as worried. That hypothetical family member would probably be vaccinated, and we’d have another year of information about the virus. I’d also have a year of stories about people who caught COVID-19 and didn’t become seriously ill, because the vaccines are so good at preventing bad cases of the disease.

Calm “comes from experience,” Taylor says.

Blind spots

Calm can also be dangerous. The trouble with marking the end of pandemics by how they feel instead of by a concrete metric is that we might set the bar for what feels like normal in an uncomfortable place. “At a certain point, there’s a concern that people might underestimate the risk,” Gidengil says. “Diseases come under control, so there is less risk, but we want to attune it so we’re at the sweet spot of understanding what the risk is so that we can make well-informed decisions.”

She saw that with H1N1. Toward the end of that pandemic, as people’s fear of the virus started to let up, Gidengil’s research showed that the number of people who wanted to get the H1N1 vaccine started to drop. The virus seemed like less of a threat, and people felt like it was less urgent to take steps that would protect them from it.

But endemic diseases, even though they seem less acutely scary, are still dangerous. Seasonal flu kills thousands of people a year in the United States. Malaria is a leading cause of death in countries where it’s endemic. Our collective anxiety might fade, but the virus will still be a clear risk. The level of regularly circulating coronavirus will layer on top of the other circulating diseases. It’ll raise the baseline number of people who get sick and die each year.

“Another killer has been added to the list of things that kill us,” Christakis says.

Right now, around 600 people a day are dying from COVID-19 in the United States. If that was the average background level of disease, it’d mean something like an additional 200,000 deaths from infectious diseases each year.

Feeling our way toward the social end of the pandemic in the US also risks turning on blinders to the way COVID-19 could continue to burn through the rest of the world. The vaccine rollout is devastatingly unequal — high-income countries locked down over half of the world’s doses, and poorer countries likely won’t be able to immunize their populations for years. Low rates of COVID-19 in the US could create an illusion of security, but outbreaks around the world mean persistent risk. “I don’t think it’s fully safe for the US while the rest of the world suffers,” Nuzzo says.

Luckily, we have a stake and some control over how the transition toward the end of the pandemic happens. Communities and their public health leadership can decide that they don’t want to normalize tens of thousands of additional deaths. They can invest money and effort and time into smothering the virus as much as possible. They can decide to say that the pandemic isn’t over in one country until it’s over everywhere.

COVID-19 isn’t going anywhere, Christakis says. “The virus is just going to keep searching for victims.” Pandemics can’t last forever, and danger doesn’t always feel like an emergency. But the number of people we’re willing to lose to the virus without alarm bells ringing is up to us.