Imperfect offerings: inside the complex new world of trans tech

In late February, a small company called Euphoria became the day’s main character in trans Twitter circles. The company tweeted an article about their suite of apps — Clarity, Solace, and Bliss — which were designed to be companions for trans people at different points in their transition. Euphoria was announcing a new round of funding from Chelsea Clinton, the Gaingels venture investment syndicate, and other investors, expressing gratitude “for the trust and confidence they’ve placed in us to continue to build more trans tech.”

The company had received very little engagement on Twitter until then. But that tweet in particular gained traction, with hundreds of people quote-tweeting to dunk on the company’s products, calling them grifts or “woke capital” and urging people to seek out community to meet their needs rather than downloading the apps. Trans artist Matt Lubchansky tweeted “my brain is in hell” alongside screenshots of the Euphoria and Gaingels Twitter profiles.

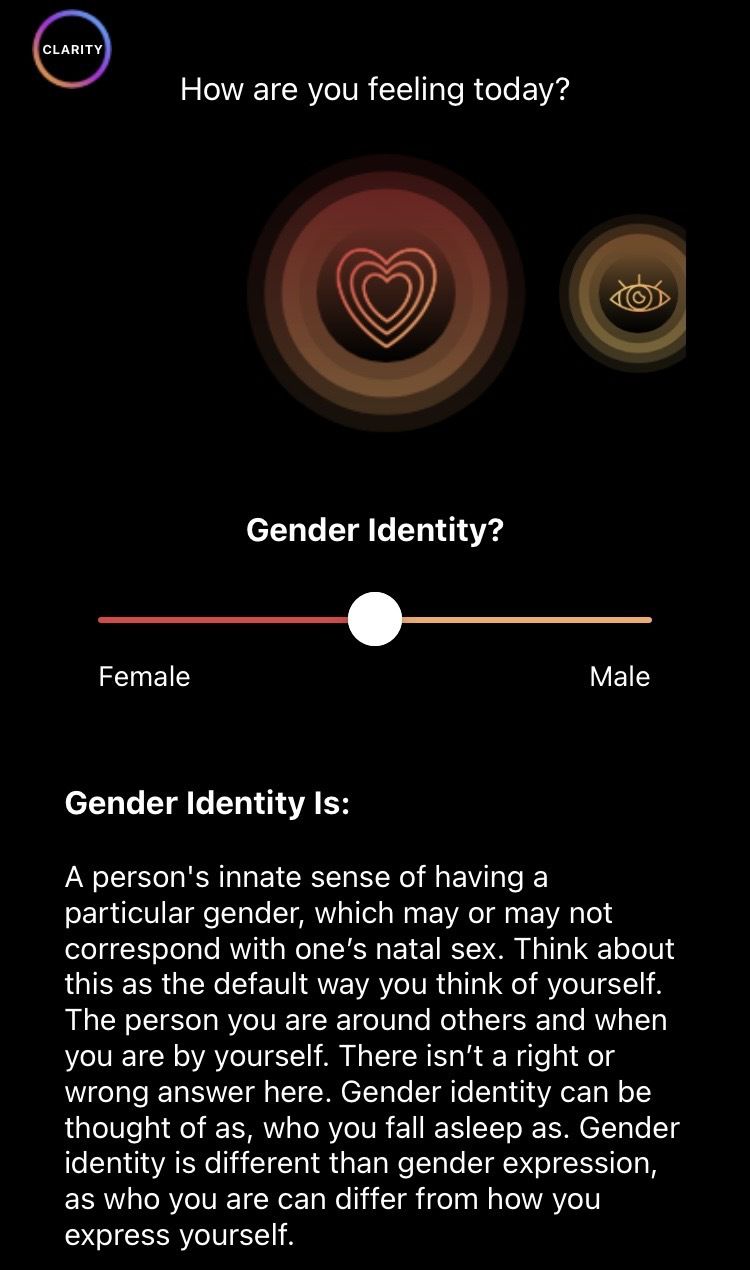

The apps themselves, sleek and butterfly-themed, look fairly innocuous. The Clarity app consists of three sliders, for gender identity, expression, and attraction, to track a person’s sense of self from day to day. Solace is a sort of guidebook to transition, with goals to choose from and information on a wide variety of transition-related topics. Bliss hasn’t launched yet but will be a savings and financial planning app for transition goals.

Most critics were skeptical: were these apps data-mining scams? Were they made to replace the function of trans communities? Because so many trans people are rejected both from family and from wider society, community ties are often critical for guidance, support, and survival. “This is yet another product to replace community, giving tips and helpful goals for all things trans, without ever needing to talk to another person,” said trans writer Niko Stratis. “I cannot stress enough that these are all things you can get from community.”

Other startups for trans people received similar pushback. Plume (which Euphoria partners with) and Folx are both subscription-based hormone services that faced scrutiny from people skeptical of venture capital solutions to health care disparities. Folx has an entire page in its FAQ section titled “Yes, Folx is VC-Funded.” There’s even a highlighted segment — “Venture capital is one of the few avenues available to take the risks necessary to tear down the current system and build anew” — that calls to mind a familiar question for queer people. How can someone dismantle a system while operating within its parameters?

Twitter users don’t reflect the entire human population, but the argument that played out was a microcosm of a larger historical conflict within queer communities. Some people want to assimilate into dominant society while others seek to liberate themselves from it entirely. That tension has been present for decades, as gay rights gained mainstream attention and pride events turned from political rallies to corporate-sponsored parades. Some trans people will accept, happily or begrudgingly, whatever tools might make their lives easier, while others reject solutions that are entangled in the same structures that have kept them ground down.

For a population that is consistently rendered socially, financially, and politically powerless, it can feel insulting to be offered a product sanctioned by the society that has robbed them of their power. Trans people who reacted with anger and disbelief to Euphoria’s offerings are coming from years of distrust for anything that bypasses community building in favor of the whims of investors and marketers.

Trans people live with constant uncertainty. Compared to the general population, trans people, especially trans women of color, are significantly more susceptible to discrimination and violence and experience higher rates of poverty, homelessness, and suicidal thoughts. Many don’t have even basic health care, let alone insurance that will cover hormone therapy or surgeries. Wave after wave of proposed legislation threatens to strip away rights, from bathroom bills to laws severely restricting young trans people’s access to gender affirming health care.

At the same time, trans people are the latest population to become marketable, targeted with rainbow products and boilerplate statements from brands that offer validation through consumerism. While trans people struggle to be more than the most frequently ignored letter of “LGBT,” corporations want to flaunt their trans acceptance to both cis and trans consumers. Communities cobble together mutual aid funds for housing, transportation, and health care while startups like Folx, Plume, and Euphoria attract attention from investors.

Robbi Katherine Anthony, or RKA, one of Euphoria’s founders, developed the apps after reflecting on her own transition, which she describes as a rocky road. She says that one of the Solace entries, titled “Loving Yourself,” is a love letter to her former self, telling other trans people the things she wishes she could have heard.

When she tried to research for certain goals early in her transition, she would find an abundance of conflicting information. It took her years to start hormone therapy, partly because “if I had to have 50 tabs open and cross reference against all of them to find the kernel of truth, I usually just kind of took a break from it, because it was so stressful.” She and her co-founder decided to start making apps with the goal to “make transition suck less.”

RKA easily brushed off the Twitter kerfuffle. “There’s a contingent of people in the trans community that are very, very opposed to capitalism, companies, for-profit services,” she says, “and will just stake out opposition to anything of that nature.” For her, claims that the apps seek to replace networks of community care don’t hold much water. She wants Solace to be one solution among many for trans people. Some people will still want to be involved in their communities and go to support groups, she says, “and as long as we don’t preclude anyone from doing that, I see us as a complimentary effort rather than an extinction event, if you will.”

For her transition, RKA preferred to do things solo rather than trying to find a community of other trans people. “At the end of the day, I’m just looking for a conformist experience,” she says. “I’m just looking to blend in. And so the idea of being part of a community felt almost opposed to my transition goals.” The apps cater to people who feel similarly, and the majority of Solace users prefer the app to community functions, she says.

Angry tweets aside, RKA says the overall response to the apps has been positive. She says surveys have shown that users find transitioning more achievable with Solace in their pocket. Most importantly, she says the company receives thousands of messages and emails from users saying their suicidal ideation has decreased. “I have had suicidal thoughts pertaining to body dysphoria, but Solace helps me realize I can’t give up,” reads one.

![A word bubble that says “Hey friend! It’s good to see you, [name]. How can I help today?” The bubble is coming from a circle that is pink in the center with concentric circles that become blue at the edge. Underneath is a simple illustration of a mountaintop with a trans flag at the top, labeled “goals and progress.”](https://thestateindia.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/1621437971_429_Imperfect-offerings-inside-the-complex-new-world-of-trans-tech.jpg)

Lilly DeLoe, who uses Solace, turned to books, internet digging, and chats with friends to find information about transition. But she says Solace was the first resource that offered “some semblance of a roadmap with a reasonable amount of variability in regards to possibilities for transition.” Like RKA, she didn’t entirely trust forums because the information shared in them could be inaccurate or overly specific to individual people. She’s been using Solace for about eight months and is amazed at the progress she’s made in her transition goals in that time. She had held off on transitioning for a long time, but she says if a comprehensive resource like Solace had existed 20 years ago, “I wouldn’t have waited until I was 39 to transition. I wouldn’t have lost 20 years of my life, pretending to be someone I wasn’t.”

Still, others are concerned that the apps signal a concerning shift toward individual-based solutions to the symptoms, rather than the causes, of inequality, and a shift away from the communal care that has often been central to trans people’s lives. Euphoria’s products are another individualized approach to the massive gaps in US health care, one of many opportunities for capitalism to pat itself on the back for addressing problems it causes, says Zein Murib, assistant professor of political science at Fordham University. People with political or financial power back apps and hormone delivery services without actually changing the system that makes gender confirmation care unobtainable in the first place.

It makes sense that people pushed back against a set of venture-backed apps that aim to solve trans people’s complex problems, Murib says. Turning to venture capital is contrary to many trans people’s desire to escape profit-based systems that have kept them marginalized by deeming them unprofitable for companies and therefore worthless. Any product that pitches itself as a guidebook for transition, no matter how nuanced and flexible, can be perceived as a call to assimilate, both into cisnormative society and the capitalist system that comes with it. “I’m not surprised that there was this big Twitter response by people saying, on one hand, not only do they not want to assimilate,” says Murib, “but also from a lot of people saying, ‘what if I can’t assimilate?’”

Solace is clear that its listed goals are not the be-all, end-all of transition, that everyone’s transition will be different and there’s no single correct way to be trans. But it still echoes white, middle class, and cisnormative ideals of what transness looks like, says Chris Barcelos, assistant professor of women’s, gender, and sexuality Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Solace is also hindered by the word count of its entries; picking and choosing which complexities are worth mentioning in its introductory summaries of topics that could (and do) fill books.

Several people pointed out that Solace is more focused on people of binary genders — woman or man — with little inclusion of nonbinary people. Binary transition narratives are usually the most palatable to cis people, and people who fall outside of that binary are often stung by the feeling that they’re an afterthought in mainstream discussions of transness, leading to tension not just between cis and trans people, but also between binary and nonbinary trans people. “We look at transgender men and transgender women as our greatest point of focus,” says RKA, “because that’s the largest chasm to cross.”

The Solace app understands transition through consumption: buy these clothes, get these surgeries, and you’ll be successfully trans, says Barcelos. Even in the goals that aren’t about consumption, the app tries to quantify things that can’t be easily distilled into a checklist, Barcelos says. Checking off goals along the path of transition can be incredibly meaningful for someone like DeLoe, but Barcelos and Murib both argue that self-surveillance and constant tracking could be harmful.

The apps are pitched together for a fixed timeline of transition. Use Clarity when you’re figuring yourself out, use Solace to identify and learn about your goals, and use Bliss to help achieve them. But transition is rarely one continuous path. Many people are out in some spaces and not others, have to stop their hormones for long stretches of time, or put off gender-affirming procedures. Some trans people have no plans to ever medically transition, or see transness as a space for experimentation with no end goal.

“Part of what contributes to transphobia and trans oppression is these essential ideas of ‘this is what trans means, this is what transition means, this is how you know you’ve completed it,’” says Barcelos. “And I think it’s dangerous to take that up and implement it in our own communities.“

Beyond the substance of the app itself, many of Euphoria’s critics took issue with the overall framing that a guide to transition is a novel idea. Trans people have been seeking and sharing information among their communities for ages. Zines like Lou Sullivan’s Information for the female-to-male crossdresser and transsexual circulated in queer social networks in the ‘80s. There were online message boards in the ‘90s. Nowadays, people turn to Discord groups, subreddits, Facebook groups, and other online forums to seek advice and find affirmation. One of the frequent calls in response to the Euphoria tweet was “if you have questions about transition, don’t download an app, DM me.”

Even before making the decision to socially or medically transition, many people turn to peers, rather than sliders on an app, for help sorting out their feelings about their identity. Transness is often explored not just in self-reflection but in conversation. “A lot of trans experience is communal,” says Alyssa Videlock, who moderates several trans-specific subreddits and Discord groups. She finds joy in helping other trans people find validation during their first moments of exploration. “They come into it and they leave with a sense of self that they didn’t have before,” she says. “Getting them to a point where they can say, ‘I’m more solid in the identity that makes me happy.’ It makes me happy to see, even if they choose not to do anything about it.”

Before she started transitioning, Kath Bigfrog, another moderator of trans groups, traveled with two other trans women to the apartment of Rita Hester, the Black trans woman whose murder sparked Transgender Day of Remembrance. They brought flowers and held a small vigil. It was in that moment, full of emotion, that Bigfrog decided, “I have to do this, I have to transition and be who I’m supposed to be.”

“Part of the problem is you can’t really make a comprehensive resource, because so much of trans community and trans history is just things that you can’t put in a guidebook,” says Bigfrog. (Author’s note: In the interest of full disclosure, I met and became friends with Bigfrog through one of the groups she moderates.) She points out that Solace actively discourages people from seeking hormones on the “grey market,” a term used for trans people sharing hormones within their communities.

Taking hormones without the guidance of a doctor can be dangerous, but trans people have a long history of sharing hormones because so few have access to gender-affirming care. There are often self-taught experts within communities who guide other trans people through hormone regimens. Euphoria’s discouragement is well-intentioned, and a smart choice to avoid liability, but the framing of its advice is aggravating for many trans people who have struggled to navigate a health care system that is so often hostile, even harmful, to them.

“If you don’t trust medical providers, you should strongly reconsider your position even if only as a matter of personal health and preservation,” says the Solace entry about the grey market. This call to action doesn’t acknowledge why many trans people are distrustful of established medical systems, assuming they can access them at all.

Faced with a history of medicine that has pathologized and traumatized them, trans people find medical advice in surprising places. “I’ve seen a bunch of posts from the same person [on Lex, a queer dating app] that are just like, ‘Oh, thanks for all the help with top surgery shit’,” says Bigfrog. “You could literally just log on to Lex and be like, ‘I want to get top surgery’ and you’ll get a bunch of gay people in your DMs telling you where to go and what to do.”

DeLoe approaches the apps from a pragmatic viewpoint. Maybe venture capital isn’t the best answer to trans people’s problems, but she at least had a concrete resource she could use to teach her therapist about transness. It’s hard to see Solace as a grift when it has materially improved the lives of DeLoe and others like her. The app is, instead, another incomplete solution that highlights the precariousness and desperation of trans existence, a response to the difficulties of life within an unjust society.

“There is a bit of a cultural rub going on right now in which solutions have to be perfect for everyone to be seen as worthwhile,” says RKA. “But in some sense, that’s a really ineffective way to make change. Because the suggestion is, don’t do anything until it’s perfect.”

There are no perfect solutions as long as transphobia is rampant and health care remains a nightmare. Even successful fundraisers for trans medical care, tangible demonstrations of community power, are tangled up in internalized biases. The crowdfunding campaigns that raise the most money are usually for young white men, and campaign descriptions are often constricted to normative understandings of transness, echoing “wrong body” narratives that appeal to cis people. “We’re both caring for each other by circulating the same $20 around in trans communities,” says Barcelos, “but also complicit in larger patterns of inequality.”

Euphoria, with its imperfect offerings, puts forth options for people who prefer to transition on their own or who are exhausted at the idea of trawling through forums to find pearls of wisdom. But community conversations, online or in person, leave room for complexity and experimentation. It’s among communities that people are able to explore their identities in more expansive terms than simplified Gender 101, where people organize calls to their representatives, discuss how much they’re willing to assimilate, strategize about fundraising, laugh, and mourn. Of her trip to Hester’s apartment, Bigfrog says, “That sort of camaraderie you can’t get from an app, you know? You ain’t sobbing over flowers with the sliders or whatever.”