The jet engine inventor's idea to help the RAF was ignored by minsters

A proposal by the future inventor of the jet engine for an interceptor fighter plane was ignored by the British government two years before the Blitz, a newly discovered memo has revealed.

Sir Frank Whittle described how his design for powering aircraft would allow the RAF to combat Luftwaffe bombers if they attempted to take over Britain’s skies.

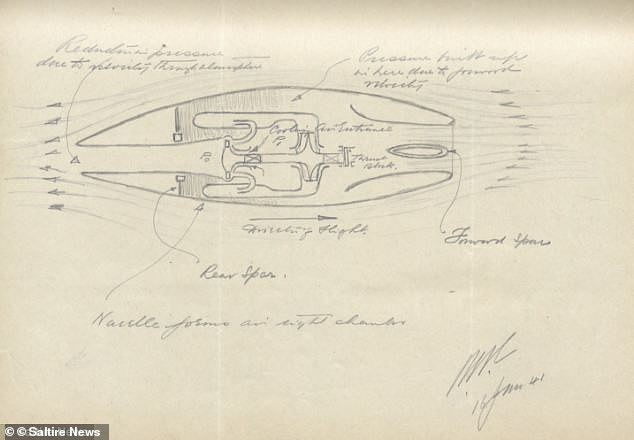

In a 1938 letter to the Air Ministry, Whittle even estimated the speeds that an aircraft powered by his engine would achieve at sea level as well as 10,000ft and 20,000ft.

‘The primary function of the interceptor fighter is to carry a pilot and his machine guns to within the vicinity of a raiding bomber for a sufficient length of time to enable him to achieve its destruction, preferably before it has reached its target,’ he said at the time.

A proposal by Sir Frank Whittle (bottom right), the future inventor of the jet engine for an interceptor fighter plane, was ignored by the British government two years before the Blitz

He believed the new fighter would have ‘so substantial an advance in performance’, that it would double the chances of a successful interception of an enemy aircraft.

But there is no record of the Air Ministry ever replying, and Britain’s ‘faffing about’ meant a six-year wait until the project, which could have saved hundreds of lives in the Blitz, being fully realised.

Now a new book detailing Whittle’s extraordinary life also looks into the missed opportunity by officials to turn a groundbreaking invention into a decisive weapon in the Second World War.

‘It’s quite a startling piece,’ Duncan Campbell-Smith, author of Jet Man, told The Times of the memo discovered in Whittle’s archive at Churchill College, Cambridge.

‘[Whittle] definitely sent it but I don’t think he ever received a reply. It encapsulates the whole story. The Brits faff about. They don’t get into it until too late in the war. The more I read, the more I realised how very badly he had been treated.’

Whittle described how his design for a new type of aircraft would allow the RAF to combat Luftwaffe bombers if they attempted to take over Britain’s skies

Though once rejected from the RAF on physical grounds, Whittle later made a successful application to the force and joined as an apprentice at RAF Cranwell in 1923.

Academically gifted, he was recommended for a cadetship and began RAF College at Cranwell, where students would write a scientific thesis every six months.

While studying, Whittle suggested the idea of a jet engine, which sucked in air, compressed and ignited it, then blasted it out of the back, propelling the plane forward.

He believed that the idea was the future of aviation and would propel planes, capable of flying at around 200mph at the time, at speeds of up to 500mph.

Even his lecturers found it difficult to comprehend, with one writing: ‘I couldn’t quite following everything you have written Whittle. But I can’t find anything wrong with it.’

The Blitz began on September 7, 1940, and was the most intense bombing campaign Britain has ever seen

But Whittle struggled to attract any interest in the inter-war period of the late 1920s, and so made his designs public by registering a patent in 1930.

Yet the RAF refused to put it on the secrets list so when the patent was granted in October 1932, engineers from the Third Reich were free to analyse the plans.

Famous German engineer Hans von Ohain would later tell him: ‘If your government had backed you sooner the Battle of Britain would never have happened.’

But the Ministry of Aircraft Production was sceptical and regarded it as a distraction from the urgent need to put enough fighters into the air to drive back the Nazis.

They did however give the project to the Rover car company, Campbell-Smith said, because some ‘very high-up people’, including Winston Churchill, had seen it and couldn’t ignore the idea completely.

But Rover never produced a engine that made it into the air.

Finally, Wilfrid Freeman, vice-chief of staff for the RAF, intervened and arranged for Rolls-Royce to take on the project. By early 1944 its engine was in the air, powering a Gloster Meteor which would reach speeds of 600mph.

Those present at a test flight were astonished to see a plane without a propeller take to the skies, and Sir Winston Churchill was said to have been so impressed that he said: ‘I want 1,000 Whittles’.

Eventually it was the Americans who would seize on the opportunities provided by the jet engine, and he would be forced by the British Government to hand over the technology.

Whittle’s son Ian, 86, recalled that his father threw everything into his work when war came.

‘When the war started he got very serious. He would disappear in his uniform in the morning and get back after I went to bed. He got so used to the British government sticking the knife into him. By 1948 his health was so destroyed that he resigned from the RAF.’

Whittle retired with the rank of Air Commodore on the grounds of ill health in 1948 and was finally recognised for his achievements.

He was knighted and awarded £100,000 (equivalent to £3.3million today) by the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors and later married American Hazel Hall and emigrated to the US, where he died in 1996.