Captain TOM MOORE recalls the warning he received before riding off in the Burmese jungle

[ad_1]

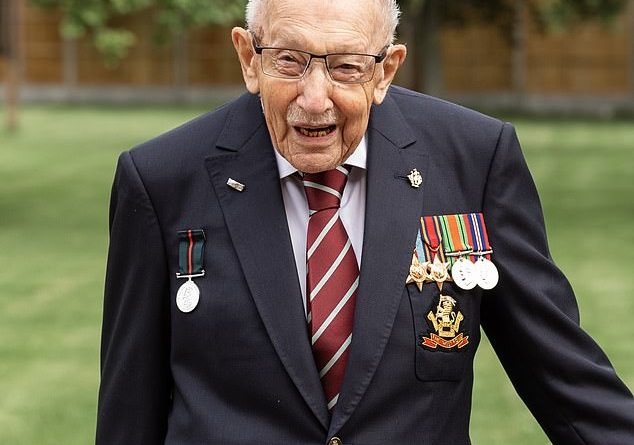

He found fame during lockdown as the 99-year-old who raised more than £32 million for NHS charities and was knighted by the Queen last month.

Now, in the second part of our exclusive serialisation of centenarian Captain Tom Moore’s memoirs, he describes how he rose through the Army ranks with his trusty motorcycle to play a vital role in the brutal war against the Japanese in India and Burma.

But however dangerous his mission, he never lost his eye for the ladies…

When I went off to war in 1940, my 81-year-old grandmother told my mother, ‘Don’t worry about our Tom. I’ll be looking after him from heaven,’ writes Captain Tom Moore

When I went off to war in 1940, my 81-year-old grandmother told my mother, ‘Don’t worry about our Tom. I’ll be looking after him from heaven.’

True to her word, ‘Granny Fanny’ as I called her (her name was Frances or Fanny Burton) was dead within a year. I like to believe she’s been looking after me ever since.

The last time I saw her, I was 20 years old and I’d just had my conscription papers ordering me to report to the Infantry Training Centre at Weston Park near Otley, 11 miles from our home at Keighley in Yorkshire.

It was a glorious summer’s day and I remember my Granny Fanny knitting socks for the armed forces in the front room as I prepared to go.

I bent to kiss her on the cheek and said, ‘Goodbye, Granny,’ but she gripped my hand, looked up into my eyes and replied firmly, ‘No, Tom. It’s goodnight.’

I squeezed her hand even tighter and gave her another quick peck, unable to speak.

Then I strapped my suitcase to the back of my motorbike. It had carried me on many thrilling rides across the moors with my tweed cap pulled down over my ears. Now it was taking me off to war.

I waved to my parents and sister, and rode to the camp at Weston Park — little more than an open field dotted with about 500 bell tents.

Captain Tom Moore is pictured middle. He served as an officer with the 145th Regiment Royal Armoured Corps from 1940

Very quickly I came to an important decision. I looked at my fellow soldiers in the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment and I looked at the officers, and I knew where my ambition lay. From that moment on, it was my intention to get a commission. After all, fortune favours the brave.

As an officer I could see that I’d have a much better life with a better uniform, and I wanted more responsibility.

I quickly learned that the regimental sergeant major was someone who could assist my ambition, so when he asked if he could borrow my motorbike to visit his ladylove, I immediately agreed.

After that, I never had to do another route march again because — if ever there was one — he made me second dispatch rider, instead.

Taking my bike to camp had served me well and that simple act followed me, for good or ill, for the next five years.

As we learned to shoot rifles and dismantle a Bren gun, I earned my first stripe and then my second, becoming a full corporal.

In March 1941, I was recommended for the OCTU or Officer Cadet Training Unit and, within six months, I had achieved my goal.

I was an officer, albeit a second lieutenant — and I was headed for active service in India on the ‘WS Convoy’… the Winston’s Special!

The temperatures in India were something that neither I nor any of my comrades in the Ninth Battalion had ever experienced.

Having survived the hustle and bustle of the Bombay quayside, we were taken to the rail-way station — teeming with people, sights, sounds and smells we could hardly credit.

Given some Indian currency, we were put on a train to Poona, a distance of 100 miles in packed carriages that crawled along painfully slowly. It did get a bit hot.

Pictured: Captain Tom serving with his battalion during the war

In the posher areas of Poona, we discovered there were a few eligible daughters of the Raj and, of course, some chaps did their best to woo them. To their surprise, the girls were old-fashioned and rather snobbish, just like their parents.

If approached in a flirtatious way, these young ladies would look the men up and down and say, ‘I can’t possibly talk to you until you have given your card to Daddy’.

There was no insecticide and the flies were everywhere. India also had an alarming array of poisonous snakes and spiders.

One night, I woke up screaming because I thought a snake was crawling across me — only to find it was nothing more than a river of sweat pouring off my chest.

We were there to train for fighting the Japanese in Burma. The plan at first was to use tanks: no one had realised yet that the jungle was ‘untankable’.

Because it was known that I understood how to operate most vehicles, I was put in charge of training men in tank warfare, even though I’d hardly ever been in one.

But it wasn’t long before the top brass worked out that tanks were next to useless in this war. What the unit urgently needed was dispatch riders to pass messages to and from the front lines. The brigadier summoned me: ‘I am appointing you Brigade Motorcycle Trainer, as of NOW!’ he said.

Most of my trainees learned fairly quickly, though some were better than others and several were downright useless. I was having the time of my life: rough terrain riding took me straight back to the Yorkshire Dales and the motorbike trials I had enjoyed in my youth.

Dispatch riders were the unsung heroes of World War II, receiving little recognition though they played a vital role in maintaining communications between headquarters and the troops, often in extreme danger.

In places such as India and Burma there were few, if any, overground telephone lines and, even if there were, these were frequently cut or damaged.

Wireless sets offered radio operators only a limited range and their messages could be intercepted, so the humble dispatch rider was often the only way to get top-secret orders and other messages through.

I warned the trainees that our maps would be often unreliable and virtually useless once the monsoons washed away tracks or turned passable roads into uncrossable bogs.

Each rider therefore had to learn the skills to navigate solo, using his wits and sense of direction, while riding ‘off road’, often under enemy fire.

At the end of each course, the trainees had to complete a test before being sent back to their battalions.

The test involved a long road trip across country, so I devised the brilliant idea of taking them the 120 miles to Bombay and back, driving there in the daylight, staying overnight and returning the following day. If they made it there and back, they passed.

I must confess to having an ulterior motive for my repeated trips to Bombay. Her name was Sylvia. She was half-Indian, half-French and the pretty younger sister of the girlfriend of a pal of mine. After I met Sylvia, I knew I had to get back to her arms as often as I could.

She was delightful, so lovely that I started rushing the men through their training just so I could get to her every weekend. Sylvia and I would go to a bar for a drink and then out for a meal before returning to the house where she lived.

It couldn’t last, of course. Bombay, or Mumbai as it is now, was on the west coast, and Burma was far to the east.

Pictured: Captain Tom, who raised millions for NHS charities, with his beloved motorcycle

My battalion was sent to Calcutta, where I went down with a bad fever. I don’t remember too much about it, but I know I spent several days in a hotel bed with a blazing temperature, a nasty headache and nobody to tend to me.

Aching all over and unable to eat, I was too ill even to take myself to a doctor but, eventually, the fever broke and I was able to rejoin my unit.

I lost so much weight that one Lieutenant Colonel, who was walking behind me, said: ‘Moore, you haven’t got a bottom. You’ve only got tops of legs.’

The unit doctor informed me that I’d had dengue fever, a viral infection spread by mosquitoes.

He said I was lucky that it hadn’t become life-threatening but I told him that having grown up in a family where you either got better or you didn’t, there was no choice to be a softie about it — or anything else.

There wasn’t much chance of that in the Army either. With a small contingent of troops, I was sent ahead of my battalion to Burma.

Shortly before we set off, we heard the distressing news that the Japanese had overrun a British main dressing station (or medical tent) in the region where we were heading.

They’d killed not only the handful of West Yorkshires guarding it, but bayoneted the doctors, orderlies and patients in a senseless act of barbarity.

Our reaction was one of rage and a renewed determination to crush the enemy. Perhaps in light of what had happened, we were each given a tablet of cyanide, a lethal dose to swallow if we were captured.

Death by poisoning must have been considered a preferable option to what the Japanese might do to us.

We were constantly on the move through jungle and across open country towards destinations I’d never heard of and likely couldn’t have pronounced if I had. Our skirmishes were many and varied in all sorts of conditions, from scrubland and paddy fields to bamboo forests and dense jungle of the Arakan.

The commander of our group was Lieutenant Colonel Richard Agnew, a Northamptonshire cavalryman from the 15th/19th King’s Royal Hussars.

One day, he summoned me and a couple of captains to inform us that the Japanese had reportedly severed the road behind us, as was their way. Agnew ordered us to go back and find out where and how badly we’d been cut off.

I remember his words as clearly as if he said them yesterday — before sending us on what seemed like a suicide mission, he a dded casually, ‘And I say, you chaps, if you get yourselves killed, I shall be very displeased with you.’

I survived and, in July 1944, I was promoted to Captain. Having done my bit in the Arakan, I was owed some leave, so I decided to take a 2,000-mile train and road trip to Gulmarg in northern India.

On my first night, sitting in the hotel bar, I met a pretty Anglo-Indian lady who reminded me of the lovely Sylvia.

Her husband, she told me, was a prisoner of the Japanese and she’d gone to Kashmir to wait for news of him. We started chatting and became friendly. I hadn’t expected to find romance in the mountains, but there it was.

In no time, I was on the front line again, with a new title: Infantry Liaison Officer. In effect, a dispatch rider who carried no dispatches or papers. I myself was the message.

There were no roads as such — just winding tracks through a bamboo forest. The belief was that if I successfully made it through several miles of bamboo and scrubland from one command post to the next, then each unit would know the path was clear.

The only way to cross that kind of terrain was on a motorbike and the skills that I had learned as a teenager, riding motorbikes on the hillsides, were the best chance I had of staying alive.

This was about to be the most dangerous period of my war. On every trip I gassed the engine and roared through the jungle as fast as I could, trying not to think about the noise my machine was making.

In this, perhaps the most dangerous time trial of all, I deployed all those tactics and used my instincts to get through.

I don’t recall ever being shot at or chased, but I was well aware that the enemy was always just out of sight through the trees, so I didn’t hang around anywhere long enough to find out. Granny Fanny must have been watching over me still.

All I had on me was my loaded Smith & Wesson revolver and a heavy radio strapped to the back of the bike with which to wireless if the road was clear — or not.

By early 1945, the Army had thought of a very different use for me. I was going back to training recruits… this time at the Royal Armoured Corps AFV School at Bovington Camp in Dorset.

A rather uninspiring colonel stuck in a hot office told me: ‘You are to train for the role of Technical Adjutant at Southern Command, Captain Moore. Once qualified, you are to train up your men with the new Churchill tanks.’

I left the East with mixed feelings, glad to be returning safely to Britain, but disappointed that I couldn’t finish the job.

By the time I was settled into my new role, the war in Europe was over. To me, that was only half the story.

My comrades were still fighting in the jungles. It wasn’t until VJ Day, marking Victory In Japan — celebrated over two days of national holiday on August 15 and 16, 1945 — that I felt real relief.

I was out of step with much of Britain. The Burma Campaign, fought in a country far, far away when so much of the focus was on Europe and Africa, never got the same attention or sympathy.

It will forever be known as the ‘Forgotten War’. But not by me. Not ever.

Tomorrow Will Be A Good Day by Captain Tom Moore, is published by Michael Joseph on September 17, £20. © Captain Tom Moore 2020.

To order a copy for £16 go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3308 9193. Free delivery on orders over £15. Promotional prices valid until September 11, 2020.

[ad_2]

Source link