How Intermittent Fasting Can Impact Your Mind, According to Experts

You know how it could affect your body, but what about your mind? Here, nutrition and psychology pros share all the ways intermittent fasting might impact your mental and emotional health.

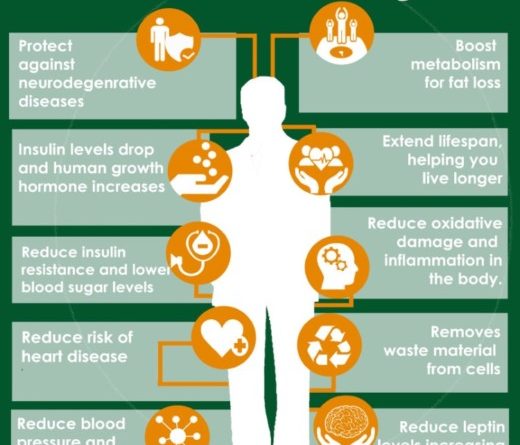

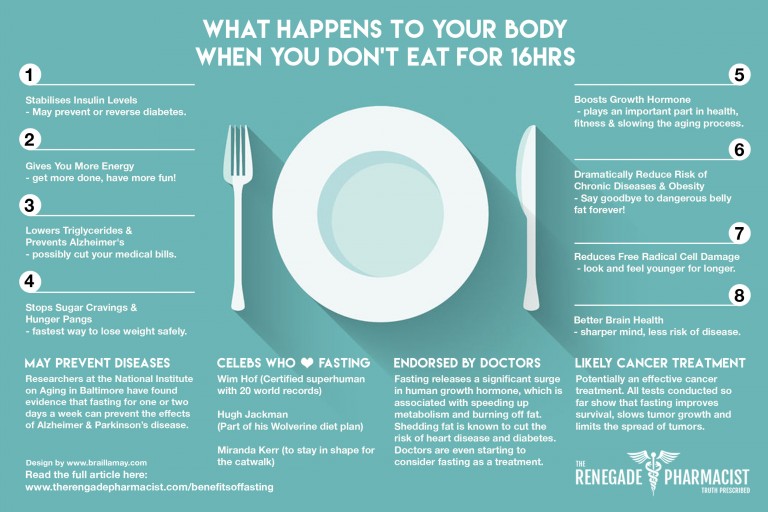

Your best friend won’t stop talking about it, your fave fitfluencer swears by it, and even Jennifer Aniston lives by it. “It” is intermittent fasting (IF)—the latest diet to make its rounds in the limelight. And with purported benefits like impressive weight loss, boosted energy, improved metabolism, better gut health, and decreased inflammation, it doesn’t seem to be leaving the wellness spotlight any time soon. (Also having a moment? The slow-carb diet.)

But before you try IF out for yourself, it’s important you know more than just how the intermittent eating plan can affect your body but also your mind. Here, experts discuss the possible psychological effects of IF.

What is intermittent fasting, again?

“Intermittent fasting cycles between periods of complete fasting, modified fasting (often very low in calories), and ‘feasting’ (days with no food restriction),” says Yasi Ansari, M.S., R.D., C.S.S.D., a registered dietitian and spokesperson for the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. “Intermittent fasting is also defined as periods of calorie restriction between periods of normal calorie intake.”

Unlike, say, keto and other popular diets, IF is best described as an eating pattern or schedule that dictates when you eat rather than what you eat. Intermittent fasting also comes in a variety of different forms that you can modify based on your schedule and needs. Here’s a breakdown of the most common types of intermittent fasting:

Alternate day fasting: Alternating between days of eating and days of fasting, during which you do not consume any food or beverages except for calorie-free drinks, such as water, coffee, and tea sans-milk.

Time-restricted daily fasting: Limiting intake to waking hours, normally without any restrictions. Fasting for 8-12 hours per day, most of which takes place during the time you’re sleeping.

- 16:8 method: One of the more popular intermittent fasting diets, this involves eating whatever you want for eight hours, then fasting for 16.

Modified weekly fasting: There are many different combinations of ways that you can choose to fast, such as…

- 5:2 method: This method involves eating normally for five days of the week and then fasting for the other two days, during which you cut back your caloric intake to 500-600 calories a day.

- 6:1 method: Similar to the 5:2 approach, but you cut back your calories or fast for only one day a week.

- 24-hour fast: This protocol requires fasting (except for sipping on calorie-free drinks) for two non-consecutive 24-hour windows twice a week.

No matter which method you choose, IF can, and likely will, impact more than just your grocery list. (Odds are all those hours sans-food will lead to fewer goodies during your next Trader Joe’s run.) While you might anticipate some physical results of intermittent fasting, you should know that IF may also have an impact on your mind.

What are the psychological effects of intermittent fasting?

It can mess with your moods.

If you’ve ever been hangry (and, tbh, who hasn’t?), you know that an empty enough stomach can give way to feelings of irritability and anger. Spend enough hours sans-food thanks to intermittent fasting and it’s very possible your mood will start to take a noticeable shift.

Feel cranky? That’s because of dropping blood sugar levels and “a spike in cortisol (the stress hormone), [which happens] when people become overly hungry,” says Susan Albers-Bowling, Psy. D, a psychologist at the Cleveland Clinic and author of Eating Mindfully and Hanger Management.

The drops—and eventual spikes when “feasting”—in blood sugar can be especially bad for those with diabetes because it can cause a lack of blood glucose control and can affect diabetes medication and insulin needs, says Ansari. (FWIW, low-carb diets like the keto diet might actually help diabetes.)

Combative? That checks out too. “There is also a hormone called neuropeptide Y that signals people to become more aggressive when they get really hungry (going back to caveman times, when you only got to eat if you were fighting or your dinner),” explains Albers-Bowling.

It might make you more anxious.

TL;DR: The more cortisol coursing through your body, the more likely it is that you’ll feel stressed. “There is some evidence [that] restricted dietary behavior can increase the stress hormone cortisol, which can cause changes in food preferences and cravings and mood,” says Ansari.

FYI- High cortisol levels have also been linked to increased fat storage, so if you’re trying to lose weight, IF can potentially work against you.

It can make you tired…

While a small pilot study found that intermittent fasting potentially improves your nightly zzz’s, other studies show that it’s more likely to cause problems with sleep. Fasting can decrease the amount of REM sleep (the super deep restorative shut-eye) due to the body’s rise in cortisol and insulin while fasting, according to a study published in the journal Nature and Science of Sleep. (Good news, though: you can actually eat your way to better sleep.)

Depending on which intermittent fasting method you choose, you might stop eating hours before bed, which can be a positive since eating close to bedtime is not great for your health, potentially causing weight gain, acid reflux and excessive gas, and difficulty sleeping. But an empty, growling stomach can make it difficult to score some shut-eye, says Michal Hertz, R.D., a dietitian in New York City.

And, let’s face it, your overall mental health relies on sufficient sleep: “Changes in sleep behavior, quality, and duration can contribute to fatigue and affect [your] mood the following day,” says Ansari.

…and lonely

“If you’re unable to eat during certain time periods, this may affect social situations with friends and family that involve food,” says Ansari. And missing out on friend time can lead to feelings of loneliness and social isolation, which can snowball into feelings of depression, according to the American Psychological Association.

Skipping out on social engagements because of diet restrictions is also a hallmark symptom of anorexia, and those with anorexia report having fewer friends, social activities, and less social support, per to the National Eating Disorders Association.

For some, it could increase the risk of developing disordered eating.

Both Albers-Bowing and Hertz agree that intermittent fasting’s strict rules about when you can and cannot eat could be triggering for someone who has a history of an eating disorder or could be at risk for a one.

“At its most basic, anorexia is about creating restrictions and rigid rules about eating, ignoring hunger and fullness, and having preoccupying thoughts about food, all of which have the potential of being perpetuated and exacerbated by IF.” (On a similar note, ever heard of orthorexia? It’s the eating disorder masking itself as a healthy diet.)

The diet may also cause “fear of loss of control (with food)” and “overeating during non-restricted days,” says Ansari. Both of which are symptoms of binge eating disorder. In fact, one study found that women who decreased their caloric intake by 70 percent for four days and then ate “normally” for three for a total of four weeks had more eating-related thoughts, increased fear of loss of control, and a frequent tendency to overeat during non-restricted hunger.

IF could also cover up an already-existing eating disorder, says Albers-Bowling. “People don’t express concern when you say, ‘Oh I’m not eating because I am on that new fasting dieting …’,”she says.

If you find that you can’t get your mind off food or are eating more than you would if you hadn’t fasted, then odds are IF isn’t for you. And if you have a history of disordered eating or a poor relationship with food, pros recommend steering clear of intermittent fasting altogether.

Bottom line: IF could be harmful to anyone’s relationship with food, but especially risky for those who have a history of disordered eating, says Hertz. “This is because they’re at a greater risk for using the rules and restrictions as a means of enabling and exacerbating their eating disorder.”

It can impact your cognitive ability.

Fasting for long periods of time can lead you to make more rash, short-term decisions, according to research.

“When you fast, you also change the neurotransmitters that are accessible in the brain,” says Albers-Bowling. “Thus, restricting foods that increase your serotonin level may also cause less of this feel-good chemical to be in your brain,” which can lead you to become more impulsive. Think: when making decisions regarding food.

Meanwhile, other research published in the International Journal of Research Studies in Biosciences that studied mice, suggests that intermittent fasting can increase levels of certain neurotransmitters—including serotonin—and strengthen learning and memory.

Clearly, there’s conflicting evidence—as is the case with much of the current research around intermittent fasting and the points in this article. Have a headache? Same. Unfortunately, there’s just a lot we don’t completely understand about IF right now.

Your perception of hunger might change.

At its very root, intermittent fasting is all about establishing mental control over hunger and, in doing so, ignoring your body’s cues that you’re hungry (which, btw, are caused by a hormone called ghrelin).

Recent research suggests that by decreasing the hunger hormone ghrelin, IF can also lower appetite and, in turn, help with weight loss. These IF-caused changes in ghrelin may also boost dopamine (pleasure hormone) levels in the brain, according to animal studies.

But “hunger is like your neighbor knocking loudly on your front door,” says Albers-Bowling. “When you try to ignore the cues, it is like your putting your hands over your ears and saying, ‘I don’t hear you, maybe if I wait they will go away.’ Hunger tends to knock even louder hoping you will respond. Eventually, hunger cues will quit knocking if you don’t respond. This damages your relationship with hunger for good.”

So, should you try IF?

Intermittent fasting isn’t for everyone—period, says Ansari. “Intermittent fasting may put certain individuals at a health risk, including people with diabetes, women who are pregnant or nursing (as inadequate nutrition can put a growing or nursing baby at risk), and those with a history of eating disorders/disordered eating.” (Related: Why You Should Give Up Restrictive Dieting Once and for All)

However, as with any eating plan, it’s a personal choice. If you do decide to go forth with intermittent fasting, Ansari recommends connecting with a registered dietitian nutritionist to ensure that you’re still “meeting your optimal nutrition needs” even on fasting days and that you continue to include a variety of food in your diet.

Also super important? Paying attention to your body including that growling stomach, says Albers-Bowling, and, of course, your mind.